| al-Mu'tasim المعتصم | |

|---|---|

| Preceded by | al-Ma'mun |

| Succeeded by | al-Wathiq |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 796 Khuld Palace, Baghdad |

| Died | January 5, 842 Samarra |

| Religion | Islam |

Abū Isḥāq Muḥammad ibn Hārūn al-Rashīd (Arabic language: أبو إسحاق عباس بن هارون الرشيد; 796 – 5 January 842), better known by his regnal name al-Muʿtaṣim bi’llāh (المعتصم بالله, "he who seeks refuge in God"), was the eighth Abbasid caliph, ruling from 833 to his death in 842.[1] A son of Harun al-Rashid, he succeeded his half-brother al-Ma'mun, under whom he had served as a military commander and governor. His reign was marked by the introduction of the Turkish slave-soldiers (ghilman or mamalik) and the establishment for them of a new capital at Samarra. This was a watershed in the Caliphate's history, as the Turks would soon come to dominate the Abbasid government, eclipsing the Arab and Iranian elites that had played a major role in the early period of the Abbasid state. Domestically, al-Mu'tasim continued al-Ma'mun's support of Mu'tazilism and its inquisition (mihna), and centralised administration, reducing the power of provincial governors in favour of a small group of senior civil and military officials in Samarra. Al-Mu'tasim's reign was also marked by continuous warfare, both against internal rebellions like the Khurramite revolt of Babak Khorramdin or the uprising of Mazyar of Tabaristan, but also against the Byzantine Empire, where the Caliph personally led the celebrated Sack of Amorium, which secured his reputation as a warrior-caliph.

Early life[]

The future al-Mu'tasim was born to the Caliph Harun al-Rashid (ruled 786–809) and Marida, a Turkic slave concubine.[1] He was born in the Khuld ("Eternity") Palace in Baghdad, but the date is unclear: according to al-Tabari, his birth was placed by various authorities either in October 796 (Sha'ban AH 180), or earlier, in AH 179 (i.e. spring 796 or earlier).[2] Al-Tabari describes the adult al-Mu'tasim as "fair-complexioned, with a black beard the hair tips of which were red and the end of which was square and streaked with red, and with handsome eyes", while other authors stress his physical strength and the fact that he was almost illiterate.[3] As one of Harun's younger sons, he was initially of little consequence.[4] During the civil war between his elder half-brothers al-Amin (r. 809–813) and al-Ma'mun (r. 813–833) he remained in Baghdad, and, like most members of the Abbasid dynasty and the Abbasid aristocracy (abnaʾ al-dawla), supported the anti-caliph Ibrahim ibn al-Mahdi in 817–819.[5] Al-Tabari records that Abu Ishaq led the pilgrimage in 816, accompanied by many troops and officials, among whom was Hamdaway ibn Ali ibn Isa ibn Maham, who had just been appointed to the governorship of the Yemen and was on his way there. During his stay in Mecca, his troops defeated and captured a pro-Alid leader who had raided the pilgrim caravans.[6] He also led the pilgrimage in the next year, but no details are known.[7]

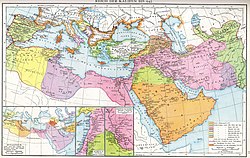

Map of the Muslim expansion and the Muslim world under the Umayyad and early Abbasid caliphates

From ca. 814/5, Abu Ishaq began forming his corps of Turkish troops. The first members of the corps were domestic slaves he bought in Baghdad (the distinguished general Itakh was originally a cook) whom he trained in the art of war, but they were soon complemented by Turkish slaves sent directly from Central Asia after an agreement with the local Samanid rulers. This private force was small—it probably numbered between three and four thousand at the time of his accession—but it was highly trained and disciplined, and made Abu Ishaq a man of power in his own right, as al-Ma'mun increasingly turned to him for assistance.[8] Abu Ishaq's Turkish corps was also politically useful to al-Ma'mun, who aimed to lessen his own dependence on the mostly eastern Iranian leaders who had supported him in the civil war, and who now occupied the senior positions in the new regime. In an effort to counterbalance their influence, al-Ma'mun granted formal recognition to his brother and his Turkish corps, as well as placing the Arab tribal levies of the Mashriq in the hands of his own son, al-Abbas.[9]

The nature and identity of al-Mu'tasim's "Turkish slave soldiers" is a controversial subject, with both the ethnic label and the slave status of its members disputed. Although the bulk of the corps were clearly of servile origin, being either captured in war or purchased as slaves, in the sources they are never referred to as slaves (mamluk or ʿabid), but rather as mawali ("clients" or "freedmen") or ghilman ("pages"), implying that they were manumitted, a view reinforced by the fact that they were paid cash salaries.[10][11] In addition, although the corps are collectively called simply "Turks", atrak, in the sources,[10] prominent early members were neither Turks nor slaves, but rather Iranian vassal princes from Central Asia like al-Afshin, prince of Usrushana, who were followed by their personal retinues (Persian chakar, Arabic shakiriyya).[12][13][14]

Al-Tabari mentions that in 819 Abu Ishaq commanded a force sent against some Kharijite rebels. During this campaign, one of the Turkish ghilman placed himself between a Kharijite lancer and the future caliph, shouting, "Recognize me!" (in Persian "ashinas ma-ra"). To express his appreciation, Abu Ishaq on that same day granted this man the name Ashinas.[15] In 828, al-Ma'mun appointed Abu Ishaq as governor of Egypt and Syria in place of Abdallah ibn Tahir, who departed to assume the governorship of Khurasan, while the Jazira and the frontier zone (Thughur) with the Byzantine Empire passed to al-Abbas.[12][16] Egypt had just been brought back under caliphal authority and pacified after the tumults of the civil war with Ibn Tahir,[17] but the situation remained volatile. When Abu Ishaq's governor, Umayr ibn al-Walid, tried to raise taxes, the Nile Delta and Hawf regions rose in revolt. In 830, Umayr tried to forcibly subdue the rebels, but was ambushed and killed along with many of his troops. With the government troops now confined to the capital Fustat, Abu Ishaq intervened in person, at the head of his 4,000 Turks. The rebels were soundly defeated and their leaders executed.[18][19] In 831, however, soon after his departure, the revolt flared up again, this time encompassing both the Arab settlers and the native Christian Copts under the leadership of Ibn Ubaydus, a descendant of one of the original Arab conquerors of the country. The rebels were confronted by the Turks, led by Afshin, who engaged in a systematic campaign, winning a string of victories and engaging in large-scale executions. Thus the male Copts were executed, and their women and children sold into slavery, while the old Arab elites who had ruled the country since the Muslim conquest of Egypt were practically annihilated. In early 832, al-Ma'mun visited the province, and soon after that the last bastion of resistance, the Copts of the coastal marshes, were subdued.[19][20]

In July–September 830, al-Ma'mun, encouraged by perceived Byzantine weakness and suspicious of collusion between Emperor Theophilos and the Khurramite rebels of Babak Khorramdin, launched the first large-scale invasion of Byzantine territory since the start of the Abbasid civil war, and sacked a number of Byzantine border fortresses.[21][22] Following his return from Egypt, Abu Ishaq joined al-Ma'mun in his 831 campaign against the Byzantines. After rebuffing Theophilos' offers of peace, the Abbasid army crossed the Cilician Gates and divided into three columns, with the Caliph, his son Abbas, and Abu Ishaq at their head. The Abbasids seized and destroyed several minor forts and the town of Tyana, while Abbas even won a minor skirmish against Theophilos in person, before withdrawing to Syria in September.[23][24] In 832 al-Ma'mun repeated his invasion of the Byzantine borderlands, capturing the strategically important fortress of Loulon, a success that consolidated Abbasid control of both exits of the Cilician Gates.[25] So encouraged was al-Ma'mun by this victory that he repeatedly rejected Theophilos' ever more generous offers for peace, and publicly announced that he intended to capture Constantinople itself. Consequently Abbas was dispatched in May to convert the deserted town of Tyana into a military colony and prepare the ground for the westwards advance. al-Ma'mun followed in July, but he suddenly fell ill and died on 7 August 833.[26][27]

Caliphate[]

On his deathbed, al-Ma'mun dictated a letter nominating his brother, rather than Abbas, as his successor.[28] This appointment owed much to Abu Ishaq's strong personality and leadership skills, but also because he was the only Abbasid prince to control independent military power in the form of his Turkish corps, on which al-Ma'mun had come to increasingly depend.[8] Consequently, Abu Ishaq was acclaimed as Caliph on 9 August, with the name of al-Mu'tasim. His position was far from secure, however, as a large part of the army favoured al-Ma'mun's son Abbas, and even tried to proclaim him as the new Caliph. Consequently al-Mu'tasim called off the expedition, abandoned the Tyana project and returned with his army to Baghdad, which he reached on 20 September.[12][29][30]

New elites and administration[]

The rise of al-Mu'tasim to the caliphate was a watershed moment in the history of the Abbasid state, heralding a radical change in the nature of its administration. Unlike his brother, who tried to use the Arabs and Turks to balance out the Iranian troops, al-Mu'tasim relied almost exclusively on his Turks, and established "a new regime that was militaristic and centred on the Turkish corps" (Tayeb El-Hibri).[13][31] This was a decision with long-lasting repercussions in Islamic history. Not only did the military acquire a predominant position, but it also increasingly became the preserve of minority groups from the peoples living on the margins of the Islamic world. Thus it formed an exclusive ruling caste, separated from the Arab-Iranian mainstream of society by ethnic origin, language, and sometimes even religion. This dichotomy would become a "distinctive feature" (Hugh N. Kennedy) of many Islamic polities, and would culminate in the great Mamluk dynasties that ruled Egypt and Syria in the late Middle Ages.[13][32] Although the new professional army proved militarily highly effective, it also posed a potential danger to the stability of the Abbasid regime: the army's separation from mainstream society meant that the soldiers were entirely reliant on their cash salary (ata) for their very survival. Consequently, any failure to provide their pay or policies that threatened their position were likely to cause a violent reaction, as became evident a generation later during the "Anarchy at Samarra". The need to cover military spending would henceforth be a fixture of caliphal government, and that at a time when government income began to decline rapidly—partly through the rise of autonomous dynasties in the provinces and partly through the decline in productivity of the lowlands of Iraq that had traditionally provided the bulk of tax revenue. Eventually, this would lead to the bankruptcy of the Abbasid government and the eclipse of the caliphs' political power with Ibn Ra'iq's rise to power in 935.[33]

Al-Mu'tasim's accession thus signalled the decline of the previous Arab and Iranian elites, both in Baghdad and the provinces, and an increasing centralisation of administration around the caliphal court. A characteristic example is that of Egypt, where the Arab settler families, who still nominally formed the country's army (jund) and continued to receive a salary from the local revenues. Al-Mu'tasim discontinued the practice, removing the Arab families from the army registers (diwan) and ordering that the revenues of Egypt be sent to the central government, which would then pay the ata only to the Turkish troops stationed in the province.[34] Al-Mu'tasim's reliance on his ghilman would increase in the aftermath of an abortive plot against him during the Amorium campaign in 838. Headed by 'Ujayf ibn 'Anbasa, a long-serving Khurasani who had served al-Ma'mun since the civil war against al-Amin, the conspiracy rallied the traditional Abbasid elites, dissatisfied with al-Mu'tasim's policies and especially his favouritism towards to the Turks. The plotters aimed to kill the Caliph and raise al-Ma'mun's son al-Abbas in his stead. According to al-Tabari, al-Abbas, although privy to these designs, rejected Ujayf's urgent suggestions to kill al-Mu'tasim during the initial stages of the campaign, and the plot was soon uncovered. Al-Abbas was imprisoned, and the Turkish leaders Ashinas, Itakh, and Bugha the Elder undertook to uncover and arrest the other conspirators. The affair was the signal for a large-scale purge of the army of the remaining senior Iranian and abnaʾ officials and commanders—according to the Kitab al-'Uyun, some seventy commanders were executed—while the influence of the Turkish leaders, who remained conspicuously loyal to al-Mu'tasim throughout the affair, correspondingly increased.[35][36] The one exception to this purge of the Iranian element were the Tahirids, who remained in place as governors of their Khurasani super-province, encompassing most of the eastern Caliphate. In addition, the Tahirids provided the governor of Baghdad, helping to keep the city, which under al-Ma'mun had been a focus of opposition to the Caliph, quiescent. The post was held throughout al-Mu'tasim's reign by Ishaq ibn Ibrahim ibn Mus'ab, who was "always one of al-Mu'tasim's closest advisers and confidants" (C. E. Bosworth).[1][37] Another departure from previous practice was al-Mu'tasim's appointment of his senior lieutenants, such as Ashinas or Itakh, as nominal super-governors over several provinces. This measure probably intended to allow his chief followers immediate access to funds with which to pay their troops, but also, in the words of H. Kennedy, "represented a further centralizing of power, for the under-governors of the provinces seldom appeared at court and played little part in the making of political decisions".[38] Indeed, al-Mu'tasim's caliphate marks the apogee of the central government's authority, in particular as expressed in its right and power to extract taxes from the provinces, an issue that had been controversial and had faced much local opposition since the early days of the Islamic state.[38]

Apart from the Turkish military and the Tahirids, al-Mu'tasim's administration depended on the central fiscal bureaucracy. As the main source of revenue were the rich lands of southern Iraq (the Sawad) and neighbouring areas, the administration was staffed mostly with men drawn from these regions. The new caliphal bureaucratic class that emerged under al-Mu'tasim were thus mostly Persian or Aramean in origin, with a large proportion of newly converted Muslims and even a few Nestorian Christians, who came from landowner or merchant families.[39] From his accession until 836, al-Mu'tasim's chief minister or vizier was his old personal secretary al-Fadl ibn Marwan, distinguished for his caution and frugality. His replacement, Muhammad ibn al-Zayyat, was of a completely different character: a rich merchant, he was, according to H. Kennedy, "a competent financial expert but a callous and brutal man who made many enemies", even among his fellow members of the administration. Nevertheless, and even though his political authority never exceeded the fiscal domain, he managed to maintain his office throughout the reign, and under al-Mu'tasim's successor al-Wathiq (ruled 842–847) as well.[1][40]

Foundation of Samarra[]

Map of Abbasid Samarra

The Turkish army was at first quartered in Baghdad, but quickly came into conflict with the remnants of the old Abbasid establishment in the city (the abnaʾ) and the city's populace, who resented their loss of influence to the foreign troops. This was a major factor in al-Mu'tasim's decision in 836 to found a new capital at Samarra, some 80 miles (130 km) north of Baghdad, but there were other considerations at play as well.[41][42] Founding a new capital was a public statement of the establishment of a new regime, while allowing the court to be "at a distance from the populace of Baghdad and protected by a new guard of foreign troops, and amid a new royal culture revolving around sprawling palatial grounds, public spectacle and a seemingly ceaseless quest for leisurely indulgence" (T. El-Hibri), an arrangement compared by Oleg Grabar to the relationship between Paris and Versailles after Louis XIV.[41][43] In addition, by creating a new city in a previously uninhabited area, al-Mu'tasim could reward his followers with land and commercial opportunities without cost to himself and free from any constraints, unlike Baghdad with its established interest groups. In fact, the sale of land seems to have produced considerable profit for the treasury: as H. Kennedy writes, it was "a sort of gigantic property speculation in which both government and its followers could expect to benefit".[41] Space and life in the new capital were strictly regimented: residential areas were separated from the markets, and the military was given its own cantonments, separated from the ordinary populace and each the home of a specific ethnic contingent of the army (e.g. the Turks, Faraghina, Maghariba and Shakiriya). The city was dominated by its mosques (most famous among which is the Great Mosque of Samarra built by Caliph al-Mutawakkil) and palaces, built in grand style by both the caliphs and their senior commanders, who were given extensive properties on the site.[41][44] Unlike Baghdad, however, the new capital was an entirely artificial creation. Poorly sited in terms of water supply and river communications, its existence was determined solely by the presence of the caliphal court, and when the capital returned to Baghdad, sixty years later, Samarra rapidly declined.[45]

Mu'tazilism and the mihna[]

Ideologically, al-Mu'tasim followed the footsteps of al-Ma'mun, continuing his predecessor's support for Mu'tazilism, a theological doctrine that attempted to tread a middle way between secular monarchy and the theocratic nature of rulership espoused by the Alids and the various sects of Shi'ism. Mu'tazilis espoused the view that the Quran was created and hence fell within the authority of a God-guided imam to interpret according to the changing circumstances. While revering Ali, they also avoided taking a position on the righteousness of the opposing sides in the conflict between Ali and his opponents.[46] Mu'tazilism was officially adopted by al-Ma'mun in 827, and in 833, shortly before his death, al-Ma'mun made its doctrines compulsory, with the establishment of an inquisition, the mihna. Al-Mu'tasim played an active role in the enforcement of the mihna in the western provinces, and continued on the same course after his accession: the chief advocate of Mu'tazilism, the head qadi Ahmad ibn Abi Duwad, was perhaps the dominant influence at the caliphal court throughout al-Mu'tasim's reign.[47][48][49] Thus Mu'tazilism became closely identified with the new regime of al-Mu'tasim, and adherence to Mu'tazilism was transformed into an intensely political issue: to question it was to oppose the authority of the Caliph as the God-sanctioned imam. While Mu'tazilism found broad support, it was also passionately opposed by traditionalists, who held that the Quran's authority was absolute and unalterable as the word of God, as well as providing a vehicle for criticism by those who disliked the new regime and its elites.[50] In the event, the active repression of the traditionalists was without success, and even proved counterproductive: the beating and imprisonment of one of the most resolute opponents of Mu'tazilism, Ahmad ibn Hanbal, in 835, only helped to spread his fame, and by the time Caliph al-Mutawakkil abandoned Mu'tazilism and returned to traditional orthodoxy in 848, the strict and conservative Hanbali school had emerged as the leading school of jurisprudence (fiqh) in Sunni Islam.[48][51]

The great Arab mathematician al-Kindi was employed by al-Mu'tasim, and tutored the Caliph's son. Al-Kindi had served at the Bayt al-Hikma, or House of Wisdom. He continued his studies in Greek geometry and algebra under the caliph's patronage.

Campaigns[]

Although al-Mu'tasim's reign was a time of peace in the Caliphate's heartland territories, al-Mu'tasim himself was an energetic campaigner, and "acquired the reputation of being one of the warrior-caliphs of Islam".[52] With the exception of the Amorium campaign, most of the military expeditions of al-Mu'tasim's reign were domestic, directed against rebels and areas that, although nominally part of the Caliphate, had remained outside effective Muslim rule and where native peoples and princes retained de facto autonomy.[52]

Domestic campaigns[]

An Alid revolt led by Muhammad ibn Qasim broke out in Khurasan in early 834, but was swiftly defeated and Muhammad brought as a prisoner to the Caliph's court. He managed to escape during the night of 8/9 October 834, taking advantage of the Eid al-Fitr festivities, and was never heard of again.[53] In June/July of the same year, 'Ujayf ibn 'Anbasa was sent to subdue the Zutt. These were people brought from India by the Sassanid emperors and settled in the Mesopotamian Marshes. The Zutt had rebelled against caliphal authority since ca. 820, and had been regularly raiding the environs of Basra and Wasit since that time. 'Ujayf was successful in encircling the Zutt and forcing them to surrender after a seven-month campaign, making a triumphal entry into Baghdad in January 835 with his numerous captives. Many of the Zutt were then sent to Ayn Zarba on the Byzantine frontier, where they fell fighting against the Byzantines.[54][55]

The first major campaign of the new reign was directed against the Khurramites in Azerbaijan and Arran.[1] The Khurramite revolt had been going on since 816/7, aided by the inaccessible mountains of the province and the absence of large Arab Muslim population centres, except for a few cities in the lowlands. Al-Ma'mun had left the local Muslims largely to their own devices, although a succession of military commanders tried to subdue the rebellion on their own initiative, and thus gain control of the country's newly discovered mineral resources, only to be defeated by the Khurramites under the capable leadership of Babak.[56] Immediately after his accession, al-Mu'tasim sent the sahib al-shurta of Baghdad and Samarra, Ishaq ibn Ibrahim ibn Mus'ab, to deal with an expansion of the Khurramite rebellion from Jibal into Hamadan. Ishaq achieved success swiftly, and by December 833 had suppressed the rebellion, forcing many Khurramites to seek refuge in the Byzantine Empire.[57] It was only in 835 that al-Mu'tasim took action against Babak when he assigned his trusted and capable lieutenant, Afshin, to command the campaign against him. After three years of cautious and methodical campaigning, Afshin was able to capture Babak at his capital of Budhdh on 26 August 837, extinguishing the rebellion. Babak was brought in triumph to Samarra, where he was executed.[58][59][60]

The second major domestic campaign was against another autonomous ruler, Mazyar of the Qarinid dynasty in Tabaristan.[61] Tabaristan had been subdued in 760, but Muslim presence was limited to the coastal lowlands of the Caspian Sea and their cities, while the mountainous areas remained under native rulers—chief among whom were the Bavandids in the eastern and the Qarinids in the central and western mountain ranges—who retained their autonomy in exchange for paying a tribute to the Caliphate.[62] With the support of al-Ma'mun, Mazyar had established himself as the de facto ruler of all Tabaristan, even capturing the Muslim city of Amul and imprisoning the local Abbasid governor. Al-Mu'tasim confirmed him in his post on his accession, but trouble soon began when Mazyar refused to accept his subordination to the Tahirid viceroy of the east, Abdallah ibn Tahir, instead insisting on paying the taxes of his region directly to al-Mu'tasim's agent.[61][63][64] Tension mounted as the Tahirids encouraged the local Muslims to resist Mazyar, forcing the latter to adopt an increasingly confrontational stance against the Muslim settlers and turn for support on the native Iranian, and mostly Zoroastrian, peasantry, whom he encouraged to attack the Muslim landowners. Open conflict erupted in 838, when his troops seized the cities of Amul and Sari, took the Muslim settlers prisoner, and executed many of them. The Tahirids in return invaded Tabaristan and in 839 captured Mazyar, who was betrayed by his brother Quhyar. Quhyar then succeeded his brother as a Tahirid appointee, while Mazyar was taken to Samarra, where he was flogged to death the next year.[61][65][66] While the autonomy of the local dynasties was maintained in the aftermath of the revolt, the event marked the onset of the country's rapid Islamization, including among the native dynasties.[67]

Mazyar's rebellion had important repercussions in Samarra. The Qarinid's intransigence had been secretly encouraged by Afshin, who hoped to discredit the Tahirids and assume their vast governorship in the east himself, but after the defeat of Mazyar, their correspondence was discovered. Already an exception among the Samarran elite due to his Iranian princely origins, and possibly suspect in the Caliph's eyes due to the independent military following he commanded, this discovery served to discredit Afshin and provided the pretext for a show trial, where he was accused, among other things, of being a false Muslim, and of being accorded divine status by his subjects in his native Ushrusana. Afshin was found guilty and thrown into prison, where he was starved to death in 841. Once more, the affair enhanced the standing of the Turkish leadership, who now received Afshin's revenue and possessions.[65][68][69] At about the same time, Minkajur al-Usrushani, whom Afshin had appointed as governor of Adharbayjan after the defeat of the Khurramites, rose up in revolt, either because he had been involved in financial irregularities, or because he had been a co-conspirator of Afshin's. Bugha the Elder marched against him, forcing the rebel to capitulate and receive a safe-passage for Samarra in 839/40.[70][71]

Near the end of al-Mu'tasim's life there were a series of uprisings in the Syrian provinces, including the revolt by Abu Harb, known as al-Mubarqa or "the Veiled One", which brought to the fore the lingering pro-Umayyad sentiment of a part of the Syrian Arabs.[1][72]

The Amorium campaign[]

Map of the Byzantine and Arab campaigns in the years 837–838, showing Theophilos's raid into Upper Mesopotamia and al-Mu'tasim's retaliatory invasion of Asia Minor, culminating in the conquest of Amorium.

Taking advantage of the Abbasids' preoccupation with the suppression of the Khurramite rebellion, the Byzantine emperor Theophilos had launched a number of attacks on the Muslim frontier zone in the early 830s, and scored a few successes. His forces were also bolstered by some 14,000 Khurramites who under their leader, Nasr, fled into the Empire, became baptized and enrolled into the Byzantine army under the command of Nasr, better known by his Christian name of Theophobos.[73] In 837, Theophilos, urged by the increasingly hard-pressed Babak, launched a major campaign into the Muslim frontier lands, with an army reportedly numbering over 70,000 men, whom he led in an almost unopposed invasion around the upper Euphrates. The Byzantines took the towns of Zibatra (Sozopetra) and Arsamosata, ravaged and plundered the countryside, extracted ransom from Malatya and other cities in exchange for not attacking them, and defeated a number of smaller Arab forces.[74][75] As refugees began arriving at Samarra, the caliphal court was outraged by the brutality and brazenness of the raids: not only had the Byzantines acted in open collusion with the Khurramites, but during the sack of Zibatra all male prisoners were executed and the rest sold into slavery, and some captive women were raped by Theophilos' Khurramites.[76][77]

The Caliph took over preparations for a retaliatory expedition himself, as the campaigns against Byzantium were customarily the only ones where caliphs participated in person.[52] Al-Mu'tasim assembled a huge force—80,000 men with 30,000 servants and camp followers according to Michael the Syrian, or even bigger according to other writers—at Tarsus, and declared his target to be Amorium, the birthplace of the reigning Byzantine dynasty. The Caliph reportedly had the name painted on the shields and banners of his army. The campaign began in June, with a smaller force under Afshin attacking through the Pass of Hadath in the east, while the Caliph with the main army crossed the Cilician Gates on 19–21 June. Theophilos, who had been caught unaware by the two-pronged Abbasid attack, tried to confront Afshin's smaller force first, but suffered a major defeat at the Battle of Dazimon on 22 July, barely escaping with his life. Unable to offer any effective resistance to the Abbasid advance, the emperor returned to Constantinople. A week later, Afshin and the main caliphal army joined forces before Ancyra, which had been left defenceless and was plundered.[78][79][80]

Byzantine envoys before al-Mu'tasim (seated, right), miniature from the Madrid Skylitzes

From Ancyra, the Abbasid army turned to Amorium, to which they laid siege on 1 August. The siege was fiercely contested, even after the Abbasids, informed by a defector, effected a breach in a weak spot of the wall. After two weeks, however, taking advantage of a short truce requested by the Byzantine commanders of the breach for negotiations, the Abbasid army stormed the city. The city was thoroughly plundered and its walls razed, while the populace, numbering into the tens of thousands, was carried off to be sold into slavery.[81][82][83] According to al-Tabari, al-Mu'tasim now pondered extending his campaign to attack Constantinople, when the conspiracy headed by his nephew, al-Abbas, was uncovered. Al-Mu'tasim was forced to cut short his campaign and return quickly to his realm, without bothering with Theophilos and his forces, encamped in nearby Dorylaion. Taking the direct route from Amorium to the Cilician Gates, both the caliph's army and its prisoners suffered in the march through the arid countryside of central Anatolia. Some captives were so exhausted that they could not move and were executed, whereupon others found the opportunity to escape. In retaliation, al-Mu'tasim, after separating the most prominent among them, executed the rest, some 6,000 in number.[84][85][86]

The sack of Amorium brought al-Mu'tasim much acclaim as a warrior-caliph and ghazi, and was celebrated by contemporaries, most notably in Abu Tammam's poems.[1] The Abbasids, however, did not follow up on their success. Warfare continued between the two empires with raids and counter-raids along the border, but after a few Byzantine successes a truce was agreed in 841. At the time of his death in 842, al-Mu'tasim was preparing yet another large-scale invasion, but the great fleet he had prepared to assault Constantinople perished in a storm off Cape Chelidonia a few months later. Following al-Mu'tasim's death, warfare gradually died down, and the Battle of Mauropotamos in 844 was the last major Arab–Byzantine engagement until the 850s.[87]

Death[]

Many of the children and grandchildren of al-Mu'tasim succeeded him on the caliphal throne

Al-Tabari states that al-Mu'tasim fell ill on 21 October 841. His regular doctor, Salmawayh ibn Bunan, whom the Caliph had trusted implicitly, had died the previous year and the new physician Yahya ibn Masawayh did not follow the normal treatment of cupping and purging, which according to Hunayn ibn Ishaq worsened the caliph's illness and brought about his death on 5 January 842, after a reign of eight years, eight months and two days according to the Islamic calendar.[88] He was buried in the Jawsaq Palace in Samarra.[89] He was succeeded by his son, al-Wathiq.

Al-Tabari describes al-Mu'tasim as having a relatively easygoing nature, being kind, agreeable and charitable,[90] while according to the Orientalist C.E. Bosworth, "Not much of [al-Mu'tasim's] character emerges from the sources, though they stress his lack of culture compared with his brother al-Ma'mun, with his questing mind; yet al-Mu'tasim's qualities as a military commander seem assured, and the Abbasid caliphate remained under him a mighty political and military entity".[1]

Al-Mu'tasim in literature[]

The name al-Mu'tasim is also used for a fictional character in the story The Approach to al-Mu'tasim by Argentine author Jorge Luis Borges, which appears in his anthology Ficciones. The al-Mu'tasim referenced there is not the Abbasid caliph, though Borges does state, regarding the original, non-fictional al-Mu'tasim from whom the name is taken: "the name of that eighth Abbasid caliph who was victorious in eight battles, fathered eight sons and eight daughters, left eight thousand slaves, and ruled for a period of eight years, eight moons, and eight days".[91]

While not strictly accurate, Borges' quote paraphrases al-Tabari, who notes that he was "born in the eighth month, was the eighth caliph, in the eighth generation from Al-‘Abbas, his lifespan was eight and forty years, that he died leaving eight sons[92] and eight daughters, and that he reigned for eight years and eight months", and reflects the widespread reference to al-Mu'tasim in the Arabic sources as al-Muthamman ("the man of eight").[93]

References[]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Bosworth 1993, p. 776.

- ↑ Bosworth 1991, pp. 208–209.

- ↑ Bosworth 1991, p. 209.

- ↑ Kennedy 2004a, p. 156.

- ↑ Kennedy 2004a, pp. 151, 156.

- ↑ Bosworth 1987, pp. 37–39.

- ↑ Bosworth 1987, p. 45.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Kennedy 2004a, pp. 156–157.

- ↑ El-Hibri 2011, pp. 288, 290.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Kennedy 2001, pp. 121–122.

- ↑ Gordon 2001, pp. 6–8.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Kennedy 2004a, p. 157.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 El-Hibri 2011, p. 296.

- ↑ Gordon 2001, pp. 7–8.

- ↑ Bosworth 1987, pp. 67–68.

- ↑ Bosworth 1987, p. 178.

- ↑ Kennedy 1998, pp. 81–82.

- ↑ Kennedy 1998, pp. 82–83.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Brett 2011, p. 553.

- ↑ Kennedy 1998, p. 83.

- ↑ El-Hibri 2011, p. 290.

- ↑ Treadgold 1988, pp. 268, 272–273.

- ↑ Bosworth 1987, pp. 186–188.

- ↑ Treadgold 1988, pp. 275–276.

- ↑ Treadgold 1988, pp. 278–279.

- ↑ Bosworth 1987, pp. 198–199.

- ↑ Treadgold 1988, pp. 279–281.

- ↑ Bosworth 1987, pp. 222–223, 225.

- ↑ Bosworth 1991, pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Treadgold 1988, p. 281.

- ↑ Kennedy 2004a, pp. 155, 156.

- ↑ Kennedy 2004a, pp. 157–158.

- ↑ Kennedy 2004b, pp. 4–5, 10–16.

- ↑ Kennedy 2004a, pp. 158–159.

- ↑ Gordon 2001, pp. 48–49, 76–77.

- ↑ Bosworth 1991, pp. xv, 121–134.

- ↑ Kennedy 2004a, pp. 159–160.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Kennedy 2004a, p. 159.

- ↑ Kennedy 2004a, pp. 160–161.

- ↑ Kennedy 2004a, p. 161.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 41.3 Kennedy 2004a, p. 163.

- ↑ Kennedy 2001, p. 122.

- ↑ El-Hibri 2011, pp. 296–297.

- ↑ El-Hibri 2011, pp. 297–298.

- ↑ Kennedy 2004a, pp. 163–164.

- ↑ Kennedy 2004a, pp. 161–162.

- ↑ El-Hibri 2011, pp. 291–292.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Bosworth 1991, p. xvi.

- ↑ Kennedy 2004a, p. 162.

- ↑ Kennedy 2004a, pp. 162–163.

- ↑ El-Hibri 2011, pp. 293–295.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 Kennedy 2004a, p. 164.

- ↑ Bosworth 1991, pp. 5–7.

- ↑ Bosworth 1991, pp. 7–12.

- ↑ Zetterstéen 1987, p. 785.

- ↑ Kennedy 2004a, pp. 164–165.

- ↑ Bosworth 1991, pp. 2–3, 7.

- ↑ Mottahedeh 1975, p. 75.

- ↑ Bosworth 1991, pp. 14–24, 36–93.

- ↑ Kennedy 2001, pp. 131–133.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 61.2 Kennedy 2004a, p. 165.

- ↑ Madelung 1975, pp. 198–202.

- ↑ Mottahedeh 1975, pp. 75–76.

- ↑ Madelung 1975, p. 204.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 Mottahedeh 1975, p. 76.

- ↑ Madelung 1975, p. 205.

- ↑ Madelung 1975, pp. 205–206.

- ↑ Kennedy 2004a, p. 166.

- ↑ Gordon 2001, pp. 77–78.

- ↑ Gordon 2001, p. 78.

- ↑ Bosworth 1991, pp. 175–178.

- ↑ Bosworth 1991, pp. 194–196, 203–206.

- ↑ Treadgold 1988, pp. 280–283.

- ↑ Treadgold 1988, pp. 286, 292–294.

- ↑ Vasiliev 1935, pp. 137–141.

- ↑ Treadgold 1988, pp. 293–295.

- ↑ Vasiliev 1935, pp. 141–143.

- ↑ Treadgold 1988, pp. 297–302.

- ↑ Vasiliev 1935, pp. 144–160.

- ↑ Bosworth 1991, pp. 97–107.

- ↑ Treadgold 1988, pp. 302–303.

- ↑ Vasiliev 1935, pp. 160–172.

- ↑ Bosworth 1991, pp. 107–117.

- ↑ Treadgold 1988, p. 303.

- ↑ Vasiliev 1935, pp. 172–173.

- ↑ Bosworth 1991, pp. 118–119.

- ↑ Vasiliev 1935, pp. 175–176, 192–193, 198–204, 284.

- ↑ Bosworth 1991, pp. 207–209.

- ↑ Bosworth 1991, p. 208.

- ↑ Bosworth 1991, pp. 210ff..

- ↑ "The Approach to al-Mu'tasim". Translated and published by Norman Thomas di Giovanni. http://www.digiovanni.co.uk/borges/the-garden-of-branching-paths/the-approach-to-al-mu%27tasim.htm. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ↑ Only six sons are listed by Ya'qubi, however: Harun al-Wathiq, Ja'far al-Mutawakkil, Muhammad, Ahmad, Ali and Abdallah. Bosworth 1991, p. 209, note 620.

- ↑ Bosworth 1991, p. 209, esp. note 621.

Bibliography[]

- Bosworth, C. E., ed (1987). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XXXII: The Reunification of the ʿAbbāsid Caliphate. The Caliphate of al-Ma'mun, A.D. 812–833/A.H. 198–213. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-88706-058-7. http://books.google.com/books?id=4J3PJZDYBMoC.

- Bosworth, C. E., ed (1991). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XXXIII: Storm and Stress along the Northern Frontiers of the ʿAbbāsid Caliphate. The Caliphate of al-Mu'tasim, A.D. 833–842/A.H. 218–227. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-0493-5. http://books.google.com/books?id=9WqdVdZWcscC.

- Bosworth, C.E. (1993). "al- Muʿtaṣim Bi ’llāh". The Encyclopedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume VII: Mif–Naz. Leiden and New York: BRILL. p. 776. ISBN 90-04-09419-9. http://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/encyclopaedia-of-islam-2/al-mu-tas-im-bi-lla-h-SIM_5656.

- Brett, Michael (2011). "Egypt". In Robinson, Chase F.. The New Cambridge History of Islam, Vol. 1: The Formation of the Islamic World, Sixth to Eleventh Centuries. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 506–540. ISBN 978-0-521-83823-8.

- El-Hibri, Tayeb (2011). "The empire in Iraq, 763–861". In Robinson, Chase F.. The New Cambridge History of Islam, Vol. 1: The Formation of the Islamic World, Sixth to Eleventh Centuries. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 269–304. ISBN 978-0-521-83823-8.

- Gordon, Matthew (2001). The Breaking of a Thousand Swords: A History of the Turkish Military of Samarra, A.H. 200–275/815–889 C.E.. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-4795-6. http://books.google.com/books?id=G1cxAkNm61IC.

- Kennedy, Hugh (1998). "Egypt as a province in the Islamic caliphate, 641–868". In Petry, Carl F.. Cambridge History of Egypt, Volume One: Islamic Egypt, 640–1517. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 62–85. ISBN 0-521-47137-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=y3FtXpB_tqMC&pg=PA62#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- Kennedy, Hugh N. (2001). The Armies of the Caliphs: Military and Society in the Early Islamic State. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-25093-5. http://books.google.com/books?id=UIspERtZEHIC.

- Kennedy, Hugh N. (2004a). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the 6th to the 11th Century (Second ed.). Harlow, UK: Pearson Education Ltd.. ISBN 0-582-40525-4. http://books.google.com/books?id=Wux0lWbxs1kC.

- Kennedy, Hugh N. (2004b). "The Decline and Fall of the First Muslim Empire". pp. 3–30. ISSN 0021-1818.

- Madelung, W. (1975). "The Minor Dynasties of Northern Iran". In Frye, R. N.. The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 4: From the Arab Invasion to the Saljuqs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 198–249. ISBN 978-0-521-20093-6. http://books.google.com/books?id=hvx9jq_2L3EC&lpg=PP1&pg=PA198#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- Mottahedeh, Roy (1975). "The ʿAbbāsid Caliphate in Iran". In Frye, R. N.. The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 4: From the Arab Invasion to the Saljuqs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 57–90. ISBN 978-0-521-20093-6. http://books.google.com/books?id=hvx9jq_2L3EC&lpg=PP1&pg=PA57#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- Treadgold, Warren T. (1988). The Byzantine Revival, 780–842. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-1462-2. http://books.google.com/books?id=3TysAAAAIAAJ.

- Vasiliev, A. A. (1935) (in French). Byzance et les Arabes, Tome I: La Dynastie d'Amorium (820–867). French ed.: Henri Grégoire, Marius Canard. Brussels: Éditions de l'Institut de Philologie et d'Histoire Orientales. pp. 195–198. http://books.google.com/books?id=jlTPAAAAMAAJ.

- Zetterstéen, K.V. (1987). "al-Muʿtaṣim bi ’llāh, Abū Isḥāḳ Muḥammad". In Houtsma, Martijn Theodoor. E.J. Brill's first encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913–1936, Volume VI: Morocco–Ruzzik. Leiden: BRILL. p. 785. ISBN 90-04-08265-4. http://books.google.com/books?id=fWNpIGNFz0IC&pg=PA785#v=onepage&q&f=false.

The original article can be found at Al-Mu'tasim and the edit history here.