| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [Source] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Battle of Carrhae, fought in 53 BC near the city of Carrhae (now Harran, Turkey), was a great battle between the Roman Republic and the Parthian empire. Commander Parthian Surena crushed the Roman invasion force led by Gen. Marcus Licinius Crassus. This was one of several battles that were to be fought between Rome and the Arsacid Dynasty. This was perhaps the greatest defeat suffered by the Romans in a long time.

Crassus, a member of the First Triumvirate and known to be the richest man in Rome, more eager for glory and riches, decided to invade the United Party without the formal consent of the Senate. Rejecting an offer of help from Artavasdes II, King of Armenia, to use its territory to invade the Parthian kingdom, Crassus marched his army straight through the desert of Mesopotamia. His army eventually met with the forces of Surena in the city of Carrhae. Despite being heavily outnumbered, the cavalry of Surena fully overcame the Roman heavy infantry, killing or capturing nearly all its soldiers. Crassus himself was killed after negotiations for a truce apparently turned violent. His death put an end to the First Triumvirate, which resulted in a civil war between Julius Caesar and Pompey.

Background

The war in Parthia was the result of a series of arrangements and political alliances formed by Crassus, Pompey the Great and Julius Caesar - the so-called First Triumvirate. Between March and April of 56 BC, meetings held in Ravenna, Lucca and the province of Cisalpine Gaul sought to reaffirm the covenant. It

Bust of Marcus Crassus

was decided that the triumvirate would support and provide resources for the command of Caesar in Gaul to influence the elections that were take place in 55 BC, which would give one second consulate to Crassus and Pompey.

Crassus made his fortune in Roman real estate and other businesses, but despite political connections and wealth, he lacked support from the populace. He was envious of the glory and popularity of his fellow triumvir Pompey the Great and Julius Caesar. Crassus knew very well that to reach the status of his colleagues he would need to win military victories and new territories for Rome. Then when receiving the command of the eastern provinces, Crassus began to plan the invasion of Parthia, which was the gateway to the riches of the east, but many Romans opposed this campaign. Cicero called this war nulla question ("unjustified"), under the pretext that Parthia had a treaty with Rome. The chief Capito had kindled strong opposition campaign failed and tried to remove from office Crassus. Despite protests and opposition, Marcus Crassus left Rome on November 14, 55 BC. Publius Licinius Crassus, the son of Crassus who fought with Caesar in Gaul, joined his father in Syria during the winter of 54-53 BC, bringing 1000 Celt horsemen from Gaul who would remain loyal to their young master until his death.

Build-Up To War

Crassus arrived in Syria at the end of 55 BC and immediately began using his immense wealth to build an army. He managed to gather a force of seven legions (about 35,000 heavy Infantry), 4,000 light infantry and 4,000 knights, including 1000 Gallic knights who Publius Crassus had brought with him. Artavasdes II of Armenia made an offer of help to the Romans, allowing them to use its territory to invade Parthia and offering to supply more than 16,000 horsemen and 30,000 foot soldiers as reinforcements. Crassus refused the offer and decided to take the long way through the desert of Mesopotamia and capture the major cities of the region. In response, the Parthian king Orodes II divided his army and took most of the troops to attack the Armenians; he left the rest of his force--about 9,000 horse archers and 1000 cataphracts under the command of General Surena to skirmish with and weaken the Roman army. Orodes did not foresee that the forces of Surena (outnumbered at least 4 to 1) would be able to defeat Crassus.

Crassus received directions from the Arab chieftain Ariamnes, who had previously assisted Pompey in his eastern campaigns. Crassus trusted Ariamnes, but Ariamnes was in the pay of the Parthians. He urged Crassus to attack at once, falsely stating that the Parthians were weak and disorganized. He then led Crassus' army into the most desolate part of the desert, far from any water. Crassus then received a message from Artavasdes, claiming that the main Parthian army was in Armenia and begging him for help. Crassus ignored the message and continued his advance into Mesopotamia. He encountered Surena's army near the town of Carrhae.

The Battle

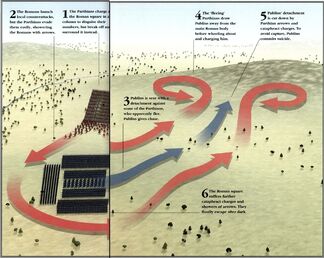

Tactic used by the Parthians at Carrhae

After being informed of the presence of the Parthian army, Crassus panicked. His general Cassius recommended that the army be deployed in the traditional Roman fashion, with infantry forming the center and cavalry on the wings. At first Crassus agreed, but he soon changed his mind and redeployed his men into a hollow square, each side formed by 12 Cohorts. This formation would protect his forces from being outflanked, but at the cost of mobility. The Roman forces advanced and came to a stream. Crassus' generals advised him to make camp and attack the next morning in order to give his men a chance to rest. Publius, however, was eager to fight and managed to convince Crassus to confront the Parthians immediately.

The Parthians went to great lengths to intimidate the Romans. First they beat a great number of hollow drums and the Roman troops were unsettled by the loud and cacophonous noise. Surena then ordered his cataphracts to cover their armor in cloths and advance. When they were within sight of the Romans, they simultaneously dropped the cloths, revealing their shining armor. The sight was designed to intimidate the Romans, but Surena was impressed by the lack of effect it had. Though he had originally planned to shatter the Roman lines with a charge by his cataphracts, he judged that this would not be enough to break them at this point. Thus, he sent his horse archers to surround the Roman square. Crassus sent his skirmishers to drive the horse archers off, but they retreated under heavy fire. The horse archers then began to shower the legionnaires with arrows. The density of the Roman formation practically guaranteed that every shot would hit, and the Parthians' composite bows were powerful enough to pierce the legionnaires' armor and partially penetrate their shields. The legionnairesw were well protected by their large shields (scuta), though these could not cover the entire body. Therefore, the majority of wounds inflicted were nonfatal hits to exposed limbs. The Romans repeatedly advanced towards the Parthians to attempt to engage in close-quarter fighting, but the horse archers were always able to retreat safely, firing Parthian shots as they withdrew. The legionnaires then formed the Testudo Formation, in which they locked their shields together to present a nearly impenetrable front to missiles. However, this formation severely restricted their ability to fight in melee combat. The Parthian cataphracts exploited this weakness and repeatedly charged the Roman line, causing panic and inflicting heavy casualties. When the Romans abandoned the formation, the cataphracts withdrew and the horse archers resumed shooting.

Crassus now hoped that his legionaires could hold out until the Parthians ran out of arrows. However, Surena

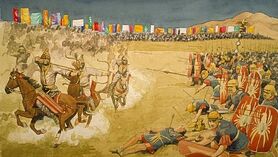

Parthian Cavalry firing arrows at the roman legions at Carrhae

used thousands of camel cavalry to resupply his horse archers. Upon realizing this, Crassus dispatched his son Publius with 1,300 Gallic cavalry to drive off the horse archers. They retreated, and after suffering heavy casualties from arrows, his cavalry were confronted by the Parthian cataphracts. The horse archers outflanked the Gauls and cut off their retreat. Publius and his men were slaughtered. Crassus, unaware of his son's fate but realizing Publius was in danger, ordered a general advance. He was confronted with the sight of his son's head on a spear. The Parthian horse archers began to surround the Roman infantry, firing on them from all directions, while the cataphracts mounted a series of charges that disorganized the Romans. The Parthian onslaught did not cease until nightfall. Crassus, deeply shaken by his son's death, ordered a retreat to the nearby town of Carrhae, leaving behind thousands of wounded, who were captured by the Parthians.

The next day Surena sent a message to the Romans, offering to negotiate with Crassus. Surena proposed a truce, allowing the Roman army to return to Syria safely, in exchange for Rome giving up all territory east of the Euphrates. Crassus was reluctant to meet with the Parthians, but his troops threatened to mutiny if he did not. At the meeting, a Parthian pulled at Crassus' reins, sparking violence. Crassus and his generals were murdered. After his death, the Parthians allegedly poured molten gold down his throat, in a symbolic gesture mocking his ' renowned greed. The remaining Romans at Carrhae attempted to flee, but most were captured or killed. Roman casualties amounted to about 20,000 killed and 10,000 captured, making the battle one of the costliest defeats in Roman history. Parthian casualties were minimal.

Aftermath

After the humiliating defeat, Rome was terribly frightened by the possibility of an invasion of the eastern territories by the Parthians. There were several wars between Rome and Parthia, with victories for both sides. But now the most significant impact of the defeat in the internal politics with the end of the first triumvirate that would put the other two triumvirs at war, would result in the end of the old Roman Republic and the birth of the Empire.

See also

The original article can be found at Battle of Carrhae and the edit history here.