The Battle of Long Tan (18 August 1966) took place near the village of Long Tan, in Phuoc Tuy Province, South Vietnam during the Vietnam War. The action was fought between Australian forces and Viet Cong and North Vietnamese units after 108 men from D Company, 6th Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (6 RAR) clashed with a force of 1,500 to 2,500 men from the Viet Cong 275th Regiment, possibly reinforced by at least one North Vietnamese battalion, and D445 Provincial Mobile Battalion. The 1st Australian Task Force (1 ATF) arrived between April and June 1966, constructing a base at Nui Dat. After two months 1 ATF had moved beyond the initial requirements of establishing itself and securing its immediate approaches, beginning operations to open the province. Meanwhile, in response to the threat posed by the Australians the 275th Regiment was ordered to move against Nui Dat. For several weeks Australian signals intelligence had tracked a radio transmitter moving westwards to a position just north of Long Tan; however, extensive patrolling failed to find the unit. At 02:43 on the night of 16/17 August Nui Dat was heavily bombarded by mortars, recoilless rifles (RCLs) and artillery fired from a position 2,000 metres (2,200 yd) to the east. Although the Viet Cong were expected to have withdrawn, a number of company patrols would be dispatched. The following morning B Company, 6 RAR departed to locate the firing points and the direction of the Viet Cong withdrawal. A number of weapon pits were subsequently found, as were the positions of the mortars and RCLs.

Around midday on 18 August, D Company took over the pursuit. At 15:40 the lead platoon clashed with a Viet Cong squad, forcing them to withdraw. Shortly after resuming the advance, 11 Platoon came under small-arms and rocket propelled grenade fire at 16:08 from a company-sized force after drawing ahead of the other platoons and was isolated. Pinned down, they called for artillery support as a monsoon rain began, reducing visibility. Beginning as an encounter battle, heavy fighting ensued as the advancing Viet Cong attempted to encircle and destroy the Australians. After less than twenty minutes more than a third of 11 Platoon had become casualties, while the platoon commander was killed soon after. 10 Platoon attempted to move up on the left in support but was repulsed. With D Company facing at least a battalion, 12 Platoon tried to push up on the right at 17:15. Fighting off an attack on their right before pushing forward another 100 metres (110 yd) they sustained increasing casualties after clashing with several groups moving around their western flank to form a cut-off prior to a frontal assault. They opened a path to 11 Platoon yet were unable to advance further and threw smoke to mark their location. With D Company nearly out of ammunition, at 18:00 two UH-1B Iroquois from No. 9 Squadron RAAF arrived overhead to resupply them. Meanwhile, the survivors from 11 Platoon withdrew back to 12 Platoon during a lull, suffering further losses. Still heavily engaged, both platoons returned to the company position covered by the artillery.

By 18:10 D Company had reformed but was still in danger of being overrun. A Company, 6 RAR was dispatched in M113 armoured personnel carriers from 3 Troop, 1st APC Squadron to relieve them. Meanwhile, B Company was still returning to base on foot and was also ordered to assist. Departing Nui Dat at 17:55, the relief force moved east, crossing a swollen creek before encountering elements of D445 Battalion attempting to outflank D Company and assault it from the rear. The Viet Cong were caught by surprise as the cavalry crashed into their flank and with darkness falling they broke through at 19:00, while B Company entered the position at the same time. Arriving at a crucial point, the relief force turned the tide of the battle. The Viet Cong had been massing for another assault which would have likely destroyed D Company, yet the firepower and mobility of the armour broke their will to fight, forcing them to withdraw. The artillery had been almost constant throughout the battle and it proved critical in ensuring the survival of D Company. By 19:15 the firing ceased and the Australians waited for another attack. However, after it became clear no counter-attack would occur, they prepared to withdraw 750 metres (820 yd) west from where their casualties could be extracted by helicopter. With the dead and wounded loaded onto the carriers D Company left at 22:45, while B and A Company departed on foot. A landing zone was then established by the cavalry with the evacuation of the casualties finally completed after midnight.

Forming a defensive position ready to repulse an expected attack the Australians remained overnight, enduring the cold and rain. They returned in strength the next day, sweeping the area and locating a large number of Viet Cong dead. Although initially believing they had suffered a major defeat, as the scale of the losses suffered by the Viet Cong were revealed it became clear they had in fact won a significant victory. Two wounded Viet Cong were killed after they moved to engage the Australians, while three were captured. The missing men from 11 Platoon were also recovered; their bodies found lying where they had fallen, largely undisturbed. Two of the men had survived despite their wounds, having spent the night in close proximity to the Viet Cong as they attempted to evacuate their own casualties. Due to the likely presence of a sizeable force nearby the Australians remained cautious as they searched for the Viet Cong. Over the next two days they continued to clear the battlefield, uncovering more dead as they did so. Yet with 1 ATF lacking the resources to pursue the withdrawing force, the operation ended on 21 August. Despite being heavily outnumbered, D Company held off a regimental assault supported by heavy artillery fire, before a relief force consisting of cavalry and infantry fought their way through and forced the Viet Cong to withdraw. Eighteen Australians were killed and 24 wounded, while the Viet Cong lost at least 245 dead which were found over the days that followed. A decisive Australian victory, Long Tan proved a major local set back for the Viet Cong, indefinitely forestalling an imminent movement against Nui Dat and challenging their previous domination of Phuoc Tuy Province. Although there were other large-scale encounters in later years, 1 ATF was not fundamentally challenged again.

Background

Military situation

III CTZ, May to September 1965.

The Australian Army Training Team Vietnam (AATTV) had been assisting South Vietnamese forces since 1962 as part of the wider US advisory effort; however, in April 1965 ground troops were committed as the worsening situation in Vietnam led to a significant escalation of the war.[1] The 1st Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (1 RAR) was dispatched with engineers, cavalry, artillery and aviation elements in support, totalling 1,400 personnel.[2] 1 RAR would be attached to the US 173rd Airborne Brigade based in Bien Hoa, a formation which operated throughout III Corps Tactical Zone (III CTZ).[3] Unlike later Australian units that served in Vietnam which included conscripts, it was manned by regular personnel only.[4] The battalion would be employed in airmobile search and destroy operations using helicopters to insert light infantry and artillery into an area of operations (AO) and support them with mobility, fire support, casualty evacuation, and resupply.[5] Commencing operations in late June, 1 RAR conducted forays into War Zone D and the Iron Triangle where they fought a number of actions including the Battle of Gang Toi on 8 November and Operation New Life in the La Nga Valley, 75 kilometres (47 mi) north-east of Bien Hoa between 21 November and 16 December.[6][7][8] Operation Marauder was launched on the Plain of Reeds in the Mekong Delta on New Years Day 1966 and continued until 7 January.[9] 1 RAR then took part in Operation Crimp in the Ho Bo Woods, north of Cu Chi over the period 8–14 January. Further fighting followed, including the Battle of Suoi Bong Trang on the night of 23/24 February 1966.[10]

At the strategic level, the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) and the South Vietnamese government had both rallied after appearing on the verge of collapse and the threat to Saigon subsided by late 1965. Yet further troop increases were required if General William Westmoreland, Commander US MACV, was to adopt a more offensive strategy, with US forces planned to rise from 210,000 in January 1966 to 327,000 by December.[11] The Australian government increased its own commitment on 8 March 1966, announcing the deployment of a two battalion brigade—the 1st Australian Task Force (1 ATF)—with armour, aviation, engineers and artillery support; in total 4,500 men. Additional Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) and Royal Australian Navy elements would also be deployed and with all three services total Australian strength in Vietnam was planned to rise to 6,300.[12] Meanwhile, 1 RAR's attachment to US forces had highlighted the differences between Australian and American operational methods. Whereas the Americans relied on massed firepower and mobility in big-unit search and destroy operations as part of a war of attrition which often resulted in heavy casualties on both sides, the Australians—although not eschewing conventional operations—emphasised deliberate patrolling using dispersed companies supported by artillery, APCs and helicopters to separate the Viet Cong from the population in the villages, while slowly extending government control.[13][14] Consequently, 1 RAR would be replaced at the end of its tour by 1 ATF which would be allocated its own Tactical Area of Responsibility (TAOR) in Phuoc Tuy Province, thereby allowing the Australians to pursue operations more independently using their own methods.[15]

By 1966 Phuoc Tuy Province was dominated by the Viet Cong. With forces dispersed across South Vietnam to defend against the growing communist insurgency, the ARVN was stretched thin with only limited resources available to counter the increasing penetration of the province.[16] Politically, Phuoc Tuy was controlled by the province chief, a South Vietnamese army officer appointed by the central government, and was divided into five districts, each with a district chief.[17] Although the government controlled Ba Ria and the Vung Tau Special Zone, it only partially controlled the village of Long Dien, the western parts of Dat Do and the villages of Long Hai, Xuyen Moc and Phu My during the day. Only the route from Ba Ria to Vung Tau was secure, and outside this area South Vietnamese forces were likely to be ambushed. Although the predominately Catholic village of Binh Gia opposed communist influence, it was isolated with the Viet Cong cadres controlling the remainder of the province, collecting taxes and subjecting the population to extortion and violent intimidation.[18] The Viet Cong increasingly operated in parallel to the South Vietnamese administration. Part of the larger communist province of Ba Long—which also encompassed Long Khanh and part of Bien Hoa Province—the Ba Long Province People's Committee co-ordinated efforts in the province under the direction of the Central Office for South Vietnam (COSVN), an organisation controlled by North Vietnam. Meanwhile, a network of cells and committees known as the Viet Cong Infrastructure provided support and extended their control into the villages and hamlets. The military forces which supported the political apparatus consisted of main forces, local forces and guerrillas.[19] Also controlled by COSVN, collectively they comprised the People's Liberation Armed Forces. Although purportedly separate from the People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN), the North Vietnamese increasingly provided reinforcements to the Viet Cong main forces, while PAVN units themselves would operate in Phuoc Tuy in later years.[20]

US paratroops during Operation Silver City, March 1966.

Lieutenant General John Wilton, the Australian Chief of the General Staff, departed for Vietnam soon after the announcement of 1 ATF's deployment, meeting senior South Vietnamese officials and US commanders, including Westmoreland, to finalise arrangements.[21] The southern-most province in III CTZ, Phuoc Tuy had been selected by the Australians because it was an area of significant Viet Cong activity, was located away from the Cambodian border, could be resupplied and, if necessary, evacuated by sea, and enabled them to concentrate their efforts in a single area to achieve greater national recognition.[15][22] Rather than being attached to a US division, negotiations between Wilton and Westmoreland ensured the force would be an independent command under the operational control of US II Field Force, Vietnam (II FFV), a corps-level headquarters based in Bien Hoa which reported directly to Commander US MACV. This would allow 1 ATF greater freedom of action and the chance to demonstrate the Australian Army's evolving operational concept for counter-insurgency warfare which had been developed, at least in part, from its experiences during the Malayan Emergency.[23] The task force would be commanded by Brigadier David Jackson, an experienced infantry officer who had served in the Middle East and New Guinea during the Second World War, and later in Korea, and commanded the AATTV and Australian Army Force Vietnam prior to taking up the appointment.[24] With the new force given less than two months to deploy hasty preparations began in Australia to ready it.[25]

Meanwhile, 1 RAR continued to operate alongside American forces.[25] Over the period 9–22 March it was involved in Operation Silver City, a two-brigade search and destroy mission 25 kilometres (16 mi) north of Bien Hoa in War Zone D under the command of the US 1st Division.[26] In late-March two brigades of the US 1st Division, reinforced by the US 173rd Airborne Brigade and a number of South Vietnamese units, conducted Operation Abilene, a search and destroy mission through Phuoc Tuy Province, targeting the 274th and 275th Regiments of the Viet Cong 5th Division, and their base areas in the May Tao Secret Zone. 1 RAR was tasked with defending a fire support and logistic base established in the Courtenay rubber plantation and later conducted a cordon and search of the village of Binh Ba. Yet the Viet Cong largely avoided battle and contact with the sweeping American brigades was light.[27] On the morning of 11 April the US 2/16th Infantry Battalion clashed with the Viet Cong D800 Battalion at Cam My in fierce close-quarters fighting during the only major action. With both sides too close for American firepower to be effective, casualties were heavy. Viet Cong losses included 41 confirmed dead and possibly another 50, while 35 Americans were killed.[28] In preparation for the arrival of 1 ATF, the population of the fortified Viet Cong village of Long Tan was forcibly removed, with the 1,000 inhabitants resettled nearby and the village destroyed by South Vietnamese forces.[26] The Australians defending the divisional fire support base were also heavily engaged, with the fighting resulting in 14 Viet Cong killed, 12 wounded and 33 captured, while 1 RAR lost four wounded.[27][29]

Terrain

Located 40 kilometres (25 mi) south-east of Saigon, Phuoc Tuy Province lay on the coast between the mountains of southern central Vietnam and the alluvial plains of the Mekong Delta, dominating the approaches to Vung Tau and the main highway to the capital.[30][31] Approximately 60 kilometres (37 mi) from east to west and 35 kilometres (22 mi) from north to south, it was roughly rectangular. Mostly flat, it gradually sloped north, while rocky hills rose in the south-west, north-east and south, including the Nui Thi Vai, May Tao and Long Hai mountains. The province was bounded to the north by Bien Hoa, Long Khanh, and Binh Tuy provinces, and to the south-east by the South China Sea.[32] Administratively separate, the Vung Tau peninsula projected south, with the city of Vung Tau at its tip including a shallow water port of strategic importance due to its capacity to relieve congestion at ports on the Saigon River. Phuoc Tuy was bisected by Route 2 running north to the provincial capital of Ba Ria, while Route 15 ran south-west between Vung Tau and Saigon and served as the main supply route for the movement of stores landed at the port, and Route 23 ran east from Baria.[33] With just a quarter of the province used for agriculture, it supported a modest population of 104,636, most of which was concentrated in the south-west in approximately 30 villages and 100 hamlets, including major settlements at Ba Ria, Long Dien, Dat Do, Binh Gia and Xuyen Moc.[34][17] Racially, the majority were Vietnamese, while there were small numbers of Chinese, indigenous Montagnards, Cambodians and French.[35] Two-thirds were Buddhist, while the remainder were Catholic.[36] Most lived in poverty as farmers, fishermen, labourers, merchants or mechanics. Rice growing was the main industry, although fruit and vegetables were also cultivated, and coastal fishing was extensive. Meanwhile, a number of charcoal kilns, sawmills, salt evaporation ponds and rubber plantations also provided employment.[17][35]

Geographically the province was ideally suited to guerrilla warfare, consisting of flat, open farmland and rice fields with numerous villages and small settlements, a long and mostly uninhabited coastline aside from the port of Vung Tau and the fishing villages of Lang Phuoc Hai and Long Hai, and a region of dense mangrove swamp and waterways in the south-west known as the Rung Sat, both of which aided infiltration. Meanwhile, isolated mountains covered in dense vegetation provided supply routes and base areas.[37] Rainforest, thick scrub and grassland covered almost three-quarters of the province, in places restricting movement of tracked and wheeled vehicles, limiting visibility to close range and providing extensive concealment. In the lowlands the vegetation provided little obstacle to either mounted or dismounted movement, although a number of watercourses and streams were difficult to traverse, particularly during the wet season, with four major rivers flowing north to south, being the Song Hoa, Song Rai, Song Ba Dap and Song Dinh. Phuoc Tuy had a tropical climate, with the monsoon lasting from mid-May to the end of October, which resulted in several hours of heavy rain up to twice a day, while the dry season lasted from October to May.[34] The Viet Cong and their predecessors, the Viet Minh, had dominated Phuoc Tuy since 1945.[38] As a consequence, the local population had a long tradition of resistance to the former French colonial administration, while communist revolutionary elements later challenged repeated attempts by the ARVN to bring the province under control of the central government in Saigon.[39] In contrast, Vung Tau was largely free from Viet Cong activity and a number of large allied military installations had been established there. A popular seaside resort with many bars and nightclubs, it was rumoured to have been used as a rest centre by both allied and Viet Cong soldiers.[40]

Prelude

Planning

III Corps Tactical Zone.

1 ATF was tasked with dominating its TAOR and conducting operations throughout Phuoc Tuy as required, as well as deploying anywhere in III CTZ and neighbouring Bihn Tuy in II CTZ on order.[41] Its principal objective was to secure Route 15 for military movement to ensure allied control of the port at Vung Tau, while politically it sought to extend government authority in Phuoc Tuy.[42] The task force would be based in a rubber plantation at Nui Dat, 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) north of Ba Ria, while a logistic base would be established in Vung Tau with a direct link forward via road.[23] Situated on Route 2, Nui Dat's central position offered short lines of communication, was close but not adjacent to the main population centres, and would allow 1 ATF to disrupt Viet Cong activity in the area.[24] Astride a major communist transit and resupply route, it was close to a Viet Cong base area yet near enough to Ba Ria to afford security to the provincial capital and facilitate liaison with the local authorities.[43] Australian doctrine emphasised establishing a base and spreading influence outwards to separate the guerrillas from the population.[44] By lodging at Nui Dat they aimed to form a permanent presence between the Viet Cong and the inhabitants.[45] 1 ATF would then focus on destroying Viet Cong forces in the province, while security of the towns and villages remained a South Vietnamese responsibility.[46] Nui Dat would be occupied in three phases. Firstly, the province chief would remove the inhabitants around the base to create a security zone. Secondly, the US 173rd Airborne Brigade would secure the area with 5 RAR, following its deployment. Finally, the main body would move forward after acclimatisation and training at Vung Tau.[47]

The task force began arriving at Vung Tau between April and June 1966.[15] From 17 May to 15 June, US and Australian forces secured the area around Nui Dat during Operation Hardihood, deploying two battalions of the US 173rd Airborne Brigade and an element of 1 RAR.[48] The Viet Cong resisted strongly, with one company of the US 1/503rd Battalion losing 12 killed and 35 wounded during a clash with a company from D445 Battalion on 17 May, while Viet Cong losses included 16 killed. The clearance of the fortified village of Long Phuoc began two days later. Located within the planned security zone, the 3,000 inhabitants were relocated following heavy fighting between two companies from D445 Battalion and the US 1/503rd Battalion and South Vietnamese forces. American losses were once again heavy; however, by 24 May the clearance was complete with Viet Cong losses including 18 confirmed killed and a further 45 estimated killed, while the dwellings, bunkers and tunnels found within Long Phuoc were destroyed. 5 RAR deployed from Vung Tau the same day and was tasked with clearing any Viet Cong found in an area 6,000 metres (6,600 yd) east and north-east of Nui Dat.[49] 1 ATF occupied Nui Dat from 5 June, with Jackson flying-in with his tactical headquarters to take command.[48] The fighting concluded on 15 June with Viet Cong losses totaling 17 killed, eight wounded and eight captured, while five Australians were killed and 15 wounded.[29] Among the dead was a National Serviceman accidentally shot on the first day of the operation—the first killed during the war.[48] Total American losses were 23 killed and 160 wounded.[50] 1 RAR returned to Australia in early June 1966, having completed 13 major operations attached to US forces for the loss of 19 killed and 114 wounded.[26]

Australians arrive at Tan Son Nhut Airport, Saigon.

The plan to operate independently resulted in significant self-protection requirements and 1 ATF's initial priorities were to establish a base and ensure its own security.[27] Meanwhile, Wilton's decision to occupy Nui Dat rather than co-locate 1 ATF with its logistic support at Vung Tau allowed the task force to have a greater impact on the Viet Cong but resulted in additional manpower demands to secure the base.[43] Indeed, the security requirements of an understrength brigade in an area of strong Viet Cong activity utilised up to half the force, limiting its freedom of action.[51] Jackson was uneasy about the possibility of a concentration against Nui Dat, fearing a major military and political setback if they succeeded in attacking 1 ATF soon after its arrival and caused heavy casualties or damage.[52][53] He subsequently moved to construct fixed defences and secure the supply route to Vung Tau, as well as implementing a high-tempo patrol program utilising infantry supported by armour, artillery and engineers.[27] Although hampered by the monsoon, defensive positions were dug, command posts sandbagged, and living areas built, while claymore mines, concertina wire and other obstacles were laid, and the vegetation cleared out to small arms range.[48] Standing patrols were established outside the base in the evening and clearing patrols sent out before stand-to every morning and evening along the 12-kilometre (7.5 mi) perimeter.[54] Daily platoon patrols and ambushes were initially conducted out to 4,000 metres (4,400 yd), which was the range of the Viet Cong mortars, but were later extended to 10,000 metres (11,000 yd) to counter the threat from artillery.[48]

As part of the occupation of Nui Dat all inhabitants within a 4,000-metre radius had been removed and resettled nearby. A protective security zone was then established, the limit of which was designated Line Alpha, and a free-fire zone declared. Although unusual for allied installations in Vietnam, many of which were located near populated areas, in doing so the Australians hoped to deny the Viet Cong observation of Nui Dat and afford greater security to patrols entering and exiting the area.[55][56] While adding to the physical security of the base, disrupting a major Viet Cong support area and removing the local population from danger,[57] such measures were unlikely to endear the Australians to those affected and may have been counter-productive.[56] Indeed the resettlement resulted in widespread resentment and it was debatable how much information the inhabitants would provide on Viet Cong movements, potentially creating an opportunity to attack Nui Dat without warning.[58][59] Meanwhile, the Viet Cong continued to observe the base from the Nui Dinh hills.[48] Movement was heard around the perimeter over the first few nights as they attempted to locate the Australian defences under the cover of darkness and heavy rain. Although no clashes occurred and the reconnaissance soon ceased, they were believed to be finalising preparations for an attack. On 10 June reporting indicated a Viet Cong regiment was moving towards Nui Dat from the north-west and was about 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) away.[60] The same day three 120 mm mortar rounds landed just outside the perimeter.[52] That night Australian artillery fired on suspected movement along Route 2, although no casualties were found the following day. Further warnings of a four-battalion attack hastened the call-forward of 6 RAR, which arrived from Vung Tau on 14 June.[60] Despite such reports no attack occurred though and the initial reaction to 1 ATF's lodgement proved unexpectedly limited.[61]

Opposing forces

Part of Military Region 1, the principal communist units operating in Phuoc Tuy were main forces from the Viet Cong 5th Division, including the 274th and 275th Regiments.[16] Under the command of Senior Colonel Nguyen The Truyen, the division was headquartered in the May Tao Mountains. Operating in Phuoc Tuy, Bien Hoa and Long Khanh it included both South Vietnamese guerrillas and North Vietnamese regulars.[62] As part of the campaign against Saigon it was tasked with isolating the eastern provinces by interdicting the main roads and highways, including national routes 1 and 15 and provincial routes 2 and 23. It this role it proved a major challenge to the ARVN, with the 275th Regiment successfully ambushing a South Vietnamese battalion near Binh Gia on 11 November 1965.[16] The 274th Regiment was the stronger and better trained of the two, operating in the Hat Dich in north-west Phuoc Tuy, it included three battalions—D800, D265 and D308—with a strength of 2,000 men. The 275th Regiment was based in the Mao Taos and mainly operated in the east of the province. Commanded by Senior Captain Nguyen Thoi Bung (aka Ut Thoi), it consisted of three battalions—H421, H422 and H421—with a total of 1,850 men.[63][64][65] In support was an artillery battalion equipped with 75 mm recoilless rifles (RCLs), 82 mm mortars and 12.7 mm heavy machine-guns, an engineer battalion, a signals battalion and a sapper reconnaissance battalion, as well as medical and logistic units.[66] Local forces included D445 Provincial Mobile Battalion, which normally operated in the south of the province and in Long Khanh. Under the command of Bui Quang Chanh (alias Sau Chanh) it consisted of three rifle companies—C1, C2, C3—and a weapons company, C4; a strength of 550 men.[67][68][Note 1] Recruited locally and operating in familiar terrain, they possessed an intimate knowledge of the AO.[69] Guerrilla forces included a further 400 men operating in groups of five to 60, with two companies in Chau Duc district, one in Long Dat and a platoon in Xuyen Moc. In total, Viet Cong strength was around 4,500 men.[16][70]

ARVN 52nd Ranger Battalion soldiers and a U.S. advisor, June 1965.

South Vietnamese forces included the relatively weak regular ARVN 52nd Ranger Battalion, as well as territorial forces consisting of 17 Regional Force (RF) companies and 47 Popular Force (PF) platoons; in total some 4,500 men.[17][71][72] Making up the bulk of government units in Phuoc Tuy, the territorial forces suffered from varying standards of training and motivation.[38] Although most villages were garrisoned by an RF company operating from a fortified compound, and PF platoons guarded most hamlets and important infrastructure, their value was questionable.[16] RF companies were technically available for operations throughout the province, while PF platoons were mostly restricted to operating around their village, yet both were primarily defensive. Although there were examples of RF and PF units successfully defending themselves, they rarely conducted offensive operations; even when they did these were usually limited and lacked initiative or aggression.[73] Mostly recruited from the same population as their opponents, they were subject to the same motivations and pressures, and often suffered equally at the hands of the Viet Cong cadre and the largely inept government. Poorly trained and unable to rely on being reinforced, the territorial forces usually provided little opposition to the Viet Cong.[18] The 90-man US Advisory Team 89 operated in support, as did a small number of Australians from the AATTV.[17] Yet despite their efforts the capabilities of the government forces remained limited.[71] Meanwhile, the arrival of 1 ATF further restricted the ability of South Vietnamese units to carry out operations in Phuoc Tuy as the Australians came to dominate the province.[74]

1 ATF consisted of two infantry battalions—5 RAR commanded by Lieutenant Colonel John Warr, and 6 RAR under Lieutenant Colonel Colin Townsend.[75] Other units included the 1st APC Squadron operating M113 armoured personnel carriers, 1st Field Regiment, Royal Australian Artillery which included two Australian and one New Zealand battery equipped with eighteen 105 mm L5 Pack Howitzers as well as six 155 mm M109 self-propelled howitzers from A Battery, US 2/35th Artillery Battalion which was permanently attached at Nui Dat, 3rd SAS Squadron, the 1st Field Squadron and 21st Engineer Support Troop, 103rd Signals Squadron, 161st Reconnaissance Flight operating Cessna 180s and Bell H-13 Sioux light observation helicopters, and an intelligence detachment.[76] Support arrangements were provided by the 1st Australian Logistics Support Group (1 ALSG) established 30 kilometres (19 mi) south at Vung Tau, while eight UH-1B Iroquois helicopters from No. 9 Squadron RAAF also operated from Vung Tau.[15] US forces also provided considerable support including medium and heavy artillery, close air support, helicopter gunships, and additional utility and medium and heavy lift helicopters.[77] The largest Australian force deployed since the Second World War, although many of 1 ATF's officers and non-commissioned personnel had extensive operational service, it had been rapidly assembled and included many untried National Servicemen. Few men had direct experience of counter-insurgency operations, and even less a first-hand understanding of the situation in Vietnam, while the task force was unable to train together before departure. Yet despite these shortfalls 1 ATF had been required to rapidly deploy and commence operations in a complex environment.[78]

Preliminary operations

National Servicemen from 6 RAR before deploying in 1966.

With 1 ATF established at Nui Dat subsequent operations included a series of search and destroy missions to gain control over Phuoc Tuy.[48] As the task force sought to extend its influence beyond Line Alpha, in early July 5 RAR patrolled north through Nui Nghe while 6 RAR cleared Long Phuoc to the south, removing a number of former inhabitants who had returned since May.[53][79] 5 RAR then began operations along Route 2, conducting a cordon and search of Duc My on 19–20 July in preparation for the clearance of Binh Ba.[80] Meanwhile, the SAS conducted long range patrols to the edge of the TAOR to provide early warning of Viet Cong concentrations.[81] Despite such measures the Viet Cong eluded 1 ATF, with the 274th and 275th Regiments believed to be in the north-west and north-east of the province. Yet with the 5th Division assessed as able to concentrate its total strength anywhere in Phuoc Tuy within 24 to 48 hours, it remained a significant threat.[52] As 1 ATF began to have an impact on the Viet Cong's freedom of action a response was increasingly expected.[82] Small-scale probes on the perimeter at Nui Dat and mortar fire had been anticipated and both had since occurred, with such activity a possible prelude to an attack. Regardless, intelligence assessments of Viet Cong intentions changed from those of May and June. Whereas previously a full-scale assault against Nui Dat was expected, as the defences were strengthened an attack against an isolated company or battalion was considered more likely. Other possibilities included continued skirmishes as part of routine patrolling and ambushing, or an attempt to interdict a resupply convoy from Vung Tau.[83]

By the end of July a large Viet Cong force had been detected by SAS patrols east of Nui Dat, near the abandoned village of Long Tan.[53] In response, 6 RAR launched a battalion search and destroy operation and during a series of fire-fights on 25 July a company from D445 Battalion bounced off C Company, and in the process of retreating assaulted B Company which was occupying a blocking position, before being driven off with heavy casualties.[84] In the following days further clashes occurred around Long Tan, resulting in 13 Viet Cong killed and 19 wounded, and Australian losses of three killed and 19 wounded. Yet with the former inhabitants resettled, the village fortified, and the perimeter regularly patrolled, the Australians considered the area secure.[53] However, with the 274th and 275th Regiments still at large, uncertainty resulted in growing tension among 1 ATF.[52] Meanwhile, believing Viet Cong sympathisers had returned to Long Tan, they planned to search the area again on 29 July. That afternoon, as 6 RAR commenced a detailed search following its initial sweep, Jackson ordered its immediate return to Nui Dat in response to South Vietnamese reports of a large Viet Cong presence close to the base, and the battalion was airlifted out by early evening.[85] Although the reports were unconfirmed and an attack against Nui Dat was considered unlikely, 1 ATF was re-postured in response. A number of company patrols were sent out in each direction over the following days, but little of significance was found. Jackson had seemed to over-react, and his requests for assistance from US II FFV were denied. Further intelligence later discredited the original reporting and the crisis soon subsided. Regardless, it was indicative of the alarms 1 ATF experienced during the first months of its lodgement and the effects they caused.[86]

In early August 5 RAR continued operations along Route 2, including the cordon and search of Binh Ba which had been postponed in late July.[87] The clearance of Binh Ba was key to opening the north of the province and linking Ba Ria to Xuan Loc in Long Khanh, yet it was dominated by the Viet Cong, and with a population of 2,100 the operation would be complex.[88] 5 RAR sealed off Binh Ba before first light on 9 August, supported by two companies from 6 RAR, as well as APCs, engineers and artillery.[87] Accompanied by South Vietnamese police, they methodically searched the village while the inhabitants were provided with food and medical aid, followed by further searches of Duc My and Duc Trung. By 10 August Binh Ba and its approaches had been cleared and the Australians commenced searching the areas east and west of Route 2. Although little contact occurred, on 14 August a group of Viet Cong approached an Australian harbour, killing one during a brief fire-fight. Regardless, Route 2 was opened to civilian traffic on 18 August.[89] By the conclusion of the operation South Vietnamese authorities had apprehended 17 Viet Cong and detained a further 77 suspects, eliminating the Binh Ba guerrilla platoon, crippling the infrastructure of the insurgency and bringing the village under government influence, with a South Vietnamese commando company later stationed there to maintain control.[90] Achieved at little cost, it was believed a significant success.[87] Warr considered cordon and search operations vital to the pacification of Phuoc Tuy, arguing they were the only way to neutralise the communist support network and were an essential first step in defeating the Viet Cong main forces even if their effectiveness relied on the questionable ability of the government to rapidly establish competent administration and security.[91]

Australian soldier during operations in Phuoc Tuy.

After two months 1 ATF had moved beyond the initial requirements of establishing itself and securing its immediate approaches, commencing operations to open the province. The Australians had penetrated the Viet Cong base areas to the east and come off the better during a number of clashes with companies from D445 Battalion. Further operations had been conducted in the Nui Dinh hills to west, while road operations along routes 15 and 23 demonstrated their viability, Binh Ba had been cleared of Viet Cong influence and Route 2 opened to civilian traffic.[92] Yet the ongoing need to secure Nui Dat reduced the combat power available to the task force commander, and it was evident that with only two battalions—rather than the usual three—1 ATF lacked operational flexibility, as while one battalion carried out operations the other was required to secure the base and provide a ready reaction force. Significant logistic problems also plagued the task force as 1 ALSG struggled to become operational amid the sand dunes at Vung Tau, resulting in shortages of vital equipment.[48] By the middle of August the Australian troops were growing tired from constant day and night patrolling with no respite from base defence duties. A program of rest and recreation began, with many granted two days leave in Vung Tau, but this further stretched the limited forces available to 1 ATF. Meanwhile, in response to the growing threat posed by the Australians the commander of the Viet Cong 5th Division finally ordered the 275th Regiment to move against Nui Dat.[87]

For several weeks Australian signals intelligence (SIGINT) had tracked a radio transmitter from the headquarters of the 275th Regiment moving westwards to a position just north of Long Tan using radio direction finding; however, extensive patrolling failed to find the unit. Provided by the top secret 547 Signals Troop, the reports began on 29 July at the height of the false alarm, with the radio detected moving towards Nui Dat from a position north of Xuyen Moc. It continued at a rate of 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) a day and by 13 August had been tracked to a position near the Nui Dat 2 feature, a hill in the vicinity of Long Tan, 5,000 metres (5,500 yd) east of Nui Dat. Although direction finding only indicated the movement of the radio, and no transmissions had been intercepted, it suggested the presence of the 275th Regiment, or at least a reconnaissance party of that unit. While deception could not be ruled out, Jackson took the threat seriously and a number of company patrols were sent out.[93] Yet the existence of a SIGINT capability was a closely guarded secret, and knowledge of the source of the reports had been limited to Jackson, his two intelligence officers, and the 1 ATF operations officer, while neither battalion commander had access to such intelligence.[94][95] On 15 August D Company, 6 RAR patrolled to the Nui Dat 2 feature and returned through the Long Tan rubber plantation. The following day A Company, 6 RAR departed on a three-day patrol on a route which included Nui Dat 2 and the ridge to the north-west. Any sizeable Viet Cong force in the vicinity would have been located, but neither patrol found anything of significance.[96] Meanwhile, SAS patrols focused on the Nui Dinh hills to the west.[97]

Viet Cong soldiers from D445 Battalion.

By 16 August the communist force was prepositioned east of the rubber plantation at Long Tan, just outside the range of the artillery at Nui Dat.[87][98] The operation was thought to have been planned by Colonel Nguyen Thanh Hong, a staff officer from the Viet Cong 5th Division who was likely in overall control.[99] Although their intentions have been debated in the years following the battle the aim was likely both a political and military victory, resolving to prove their strength to the local population and undermine Australian public support for the war.[100][101][102] The Viet Cong would probably have known one of 1 ATF's battalions was involved in the search of Binh Ba and may have considered Nui Dat weakly defended as a result.[103] Undetected, the force likely consisted of three battalions of the 275th Regiment with approximately 1,400 men, possibly reinforced by at least one regular North Vietnamese Army battalion, and D445 Battalion with up to 350 men.[98][104][Note 2] Well armed, they were equipped with AK 47 and SKS assault rifles, RPG-2 rocket propelled grenades, light machine-guns, mortars and RCLs.[98][105] Large quantities of ammunition were also carried, with each man issued two or three grenades, and grenadiers as many as 10 or 12, as well as a reserve of small arms ammunition, mortar bombs and additional rounds for the crew-served weapons.[106] Meanwhile, the 274th Regiment was probably located 15 to 20 kilometres (9.3 to 12.4 mi) north-west, occupying a position on Route 2 to ambush a squadron of the US 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment which they anticipated would move down the inter-provincial highway from Long Khanh to support the Australians.[98][107]

Battle

Opening moves, 16/17 August 1966

Battle of Long Tan, 18 August 1966

At 02:43 on the night of 16/17 August Nui Dat was heavily bombarded by the Viet Cong, and was hit by over 100 rounds from several 82 mm mortars, 75 mm RCLs and an old Japanese 70 mm howitzer fired from a position 2,000 metres (2,200 yd) to the east.[48] Most of the infantry were deployed at the time, with 5 RAR still engaged on Operation Holsworthy, although a small stay behind party remained. A Company, 6 RAR was still on patrol in the north-east of the TAOR, while a platoon from C Company was manning a night ambush to the south-east.[97] Continuing for 22 minutes, it damaged a number of vehicles and tents and wounded 24 men, one of whom later died.[87][108] The impact was spread over the south and south-east, with the 103rd Field Battery heaviest hit.[109] Despite coming under fire, the guns from the 1st Field Regiment, RAA were quickly brought into action, commencing a counter-battery mission at 02:50.[110] Yet with the artillery locating radar suspected of being faulty this had to be done using compass bearings on sound and flash. After plotting the likely firing point, a regimental fire mission of 10 rounds was fired from each gun totalling 240 rounds, and the mortaring ceased.[109] With the attack over the Australians remained alert in case of a ground assault; however, no follow up occurred. Regardless, the artillery continued to shell suspected firing positions and withdrawal routes until 04:10.[110] Although the Viet Cong were expected to have withdrawn, a number of company patrols would be dispatched the following morning to search the area east of Nui Dat in response.[48][111]

Townsend ordered B Company under Major Noel Ford to prepare for a patrol to locate the firing points which were believed to be within an area between the abandoned villages of Long Tan and Long Phuoc, and the Nui Dat 2 feature. Having done so, the patrol was to establish the direction of the Viet Cong withdrawal. Meanwhile, C Company was to provide a platoon mounted in APCs to investigate a suspected base plate location south-west of Nui Dat. A Company would also continue its patrol in the vicinity of Nui Dat 2, while 7 Platoon, C Company—already conducting a night ambush on the southern edge of the TAOR—would search a number of sites as it returned that morning.[97] No SAS patrols were deployed as a result of the overnight attack, although several had previously been planned to the north between Binh Ba and the Courtenay plantation in preparation for upcoming operations, and the program remained unchanged. Another patrol was scheduled near the Song Rai, 16 kilometres (9.9 mi) north-east of Nui Dat, and it also went ahead. Soon after insertion on the morning of 17 August it noted signs of significant activity, locating several trails moving west made approximately six hours earlier, possibly by a Viet Cong logistic unit. Yet the patrol was compromised and due to radio interference and faulty equipment the information was unable to be reported until its extraction two days later.[97] Regardless, Australian intelligence continued to assess a ground attack against Nui Dat as unlikely.[96] But with the bombardment a likely indicator of further offensive action against 1 ATF, Jackson felt he would be unable to adequately respond with only one battalion. 5 RAR was ordered to return to Nui Dat as a result and was expected back by 18 August.[111][112]

Although SIGINT had earlier alerted Jackson to the possible presence of a strong Viet Cong force in the vicinity of the Nui Dat 2 feature, patrols of the area revealed nothing and as a consequence B Company did not expect to meet significant opposition. Stepping off early on 17 August they believed they would not be staying out long and were only lightly equipped in patrol order, lacking sleeping gear and rations. With just 80 men—including many due to commence leave in Vung Tau the following day—they were significantly under-strength.[113] Crossing the swollen Suoi Da Bang creek, they soon located the firing point of the mortars as well as signs of their withdrawal as they pushed further east.[48] Meanwhile, A Company, 6 RAR under Captain Charles Mollison, continued its patrol north of the Nui Dat 2 feature, and was involved in three minor clashes with small groups of Viet Cong, killing one and wounding two.[114] B Company was subsequently tasked to remain in the area to search to the north and east the following day and was met by porters that afternoon to supply them with rations. 9 Platoon, C Company returned to Nui Dat with nothing to report, leaving A and B Companies to harbour in their night locations.[115] Speculation about the size of the communist units in the area increased. Captain Bryan Wickens, the 6 RAR Intelligence Officer, assessed that the Viet Cong's use of medium mortars, RCLs and artillery likely indicated the presence of a significant force.[116] Due to growing uncertainty about Viet Cong intentions Jackson agreed that the patrol scheduled for 18 August should be increased from a platoon to company size.[111] D Company, 6 RAR under the command of Major Harry Smith had previously been detailed for a three-day patrol south-east of Nui Dat and was instead ordered to relieve B Company the next day to continue the search.[115] Despite this neither Townsend nor Smith were warned of the possible presence of the 275th Regiment.[117]

Patrolling east of Nui Dat, 18 August 1966

After unexpectedly spending the night in the bush, the following morning B Company released the men scheduled to go on leave to return to Nui Dat. At 07:05 the depleted company, by then reduced to a single platoon and Company Headquarters, continued the search east as far as the edge of the rubber plantation, while A Company searched down the Suoi Da Bang towards their position.[115] A number of weapon pits were subsequently located, as were the firing positions of the mortars and RCLs, while discarded clothing and bloodstains found nearby confirmed the accuracy of the Australian and New Zealand artillery.[118] At Nui Dat D Company, 6 RAR began preparations for its patrol, test firing weapons and packing equipment. Despite the earlier bombardment only the standard ammunition load would be carried.[119] Lightly armed, the Australian riflemen carried just 60 rounds for their L1A1 Self-Loading Rifles and M16 rifles, and 200 rounds for each M60 machine-gun.[120] Smith was briefed by Wickens who highlighted the likely presence of a Viet Cong force equipped with mortars, assessing that it would be incapable of mounting an ambush due to the effect of the earlier counter-battery fire. While the size of the force was unknown it was not considered to be small and the possibility it was part of a larger force preparing to move against Nui Dat could not be discounted. The Viet Cong were believed to be able to attack a company-sized force and to launch mortar attacks similar to that the previous morning.[121] Smith then discussed the patrol with Townsend. If B Company had located the withdrawal route used by the mortar crews, he was to follow it with the aim of interdiction; otherwise he was to continue the search until the track was located. Assuming D445 Battalion to be the only Viet Cong unit in the area from the information available, Smith believed they were looking for that unit's heavy weapons platoon of approximately 30 to 40 men. He briefed his platoon commanders accordingly, although he also felt the Viet Cong would have long since left the area.[122] Meanwhile, 5 RAR (minus one company) returned to Nui Dat.[112]

D Company, 6 RAR departed Nui Dat at 11:00 on 18 August. Led by Smith and accompanied by a three-man New Zealand forward observer party under Captain Morrie Stanley, the 108-man company set-off quickly. Already behind schedule and with B Company having been out for longer than expected, Smith wanted to relieve Ford before more time elapsed and then follow the Viet Cong tracks to continue the pursuit that afternoon.[123] Opting for speed, he adopted single file, with 12 Platoon under Second Lieutenant David Sabben in the lead.[124] Despite the heat the company moved at a fast pace, traversing the low scrub, swamp and paddy fields as they closed in on B Company's position.[123] Meanwhile, the rock and roll acts Little Pattie and Col Joye and the Joy Boys had flown into Nui Dat and were setting up for the afternoon's concert.[125] Many of the Australians were disappointed at the prospect of missing the entertainment, and as they patrolled east they could occasionally hear the music through the trees.[123] At 13:00 that afternoon D Company married up with B Company on the edge of the Long Tan rubber plantation, approximately 2,500 metres (2,700 yd) from Nui Dat. D Company moved into a position of all round defence and sentries were posted. While the soldiers had lunch, Smith and Ford took a small protection party and inspected the area. The position appeared to have been used by the Viet Cong as a staging area prior to the bombardment two nights before, while signs of casualties having been loaded into carts and evacuated were also located. Blood stains were also uncovered, as was a quantity of equipment and sandals.[122] The mortar and RCL firing locations were also examined.[124] After briefing Smith, Ford and the remainder of B Company returned to Nui Dat.[126] D Company subsequently took over the pursuit. Smith had noted signs of a fresh track leading north-east; deciding to follow it, he called his platoon commanders in for orders.[122]

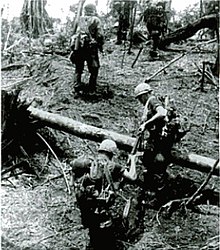

Setting off into the rubber plantation at 15:00, D Company paralleled a well-defined track which followed a slightly uphill course, with one platoon forward and two back. 11 Platoon—under Second Lieutenant Gordon Sharp—was in the lead, followed by Company Headquarters, with 10 Platoon on the left under Second Lieutenant Geoff Kendall, and 12 Platoon on the right. Each platoon moved in open formation, with two sections forward in arrowhead and one back on a frontage of approximately 160 metres (170 yd). Moving deeper into the plantation, the older trees and patchy undergrowth gave way to clean straight rows of trees which afforded long views in one direction, but limited visibility in other directions.[122][126] After 200 metres (220 yd) the track divided into two, both of which roughly ran east-south-east in parallel, 300 metres (330 yd) apart.[126] At the track junction D Company found evidence of the Viet Cong mortars having been prepared for firing, while further equipment was found scattered which again indicated a rapid withdrawal and the accuracy of the counter-battery fire. Unable to cover both tracks, Smith radioed Townsend. After discussing the situation it was decided D Company would take the more easterly track, towards the limit of the range of their covering artillery.[127] Considering the terrain, Smith adopted a "two up, one back" formation, with 10 Platoon on the left and 11 Platoon on the higher ground on the right. Company Headquarters would be central with 12 Platoon following to the rear.[126] Well dispersed with about 10 metres (11 yd) between each soldier, the company had a total frontage of 400 metres (440 yd) and was about the same in depth.[127] Amid the rubber observation was between 150 to 200 metres (160 to 220 yd), allowing visual contact between Smith and his platoons. This spacing was standard for the Australians in such terrain, yet was larger than that usually adopted by ARVN and US units.[128]

Initial contact

D Company set off again. Shortly afterwards 11 Platoon's lead section crossed a dirt road running south-west to north-east. Straight, well-established and sunken with a clearing on either side, it was 20 to 30 metres (22 to 33 yd) wide and required the Australians to complete an obstacle-crossing drill as they traversed it. At 15:40, just as the forward sections entered the tree line on the other side but before platoon headquarters could follow, a group of six to eight Viet Cong approached their right flank along the track from the south. Unaware of their presence, the Viet Cong squad continued into the middle of the now divided platoon. One was soon wounded in a brief action after the platoon sergeant, Sergeant Bob Buick, engaged them, while the remainder scattered.[127] They withdrew rapidly south-east, and although the Australians believed it to be just another fleeting contact, artillery was called-in onto their likely withdrawal route 500 metres (550 yd) south.[129] After pausing to reorganise, 11 Platoon moved into extended line, sweeping the area on a broad front in pursuit. The Australians recovered an AK 47 and the body of a Viet Cong soldier killed in the contact. Sharp reported to Smith that the Viet Cong had been dressed in khaki uniforms and pith helmets and were carrying automatic weapons, yet soldiers from D445 Battalion typically wore black and were equipped with bolt action rifles or carbines of US origin. At the time only main force units were equipped in such a manner, but the significance of this was not immediately apparent to the Australians as they attempted to follow up. With the area clear following the initial contact, Smith ordered D Company to continue their advance.[127] Meanwhile, Second Lieutenant David Harris was at Headquarters 1 ATF at Nui Dat when the first reports came in. As Jackson's aide he was aware of the intelligence being received and was convinced D Company had clashed with a main force regiment. Harris alerted Jackson, before telephoning Major Bob Hagerty—officer commanding 1st APC Squadron—to warn him of the possible requirement for his standby troop.[130]

The site of the battle in 2005.

Moving forward again, D Company continued east. 11 Platoon's rapid follow-up had opened a 500-metre (550 yd) gap with Company Headquarters, while the two lead platoons were now also widely dispersed.[118] 11 Platoon penetrated further into the plantation, widening the gap with 10 Platoon, and they were now more than 300 metres (330 yd) apart. Although 12 Platoon in the rear covered most of the ground bypassed by the forward platoons, the gap was such that their flanking sections had lost sight of each other, while Smith was unable to see them either in the dense vegetation. At that distance the spacing between the Australians was now greater than the maximum effective range of their rifles and machine-guns. Meanwhile, 11 Platoon had moved forward approximately 250 metres (270 yd) from the first engagement.[130] As Smith reached the site of the initial contact the sound of firing continued to the front as Sharp manoeuvred his sections in pursuit of the withdrawing force.[131] Still in extended line, 11 Platoon came across a rubber tapper's hut, and believing sounds emanating from the building were from Viet Cong hiding there, Sharp launched a platoon attack. Yet the Viet Cong had fled prior to the attack, and the assaulting sections swept through the area finding only two grenades.[130][131] Advancing with three sections abreast—6 Section on the left, 4 Section in the centre and 5 Section on the right—the Australians pushed on through the rubber towards a clearing. This formation allowed them to cover a broad front but offered little flank security.[131]

At 16:08, shortly after resuming the advance, 11 Platoon's left flank was engaged by machine-gun fire from an undetected Viet Cong force, killing and wounding several men from 6 Section.[118] Thy went to ground and adopted firing positions, only to be engaged by a second machine-gun firing tracer. The initial firing lasted two to three minutes then stopped, and Sharp then ordered 5 Section to sweep across the front of the platoon from the right.[132] Yet just as they began to move, the Australians came under heavy small-arms fire and rocket propelled grenades from their front and both flanks.[133] Pinned down by the weight of fire, and under threat of being overrun, the isolated platoon was forced to fight for their lives.[118] Over the next 10 to 15 minutes the Viet Cong engaged 11 Platoon with devastating fire, which put their left flank out of action. At that moment a heavy monsoon rain began which reduced visibility to just 50 metres (55 yd) and turned the ground to mud. Assessing the Viet Cong to be in greater strength than previously thought and believing they were preparing for an assault on his position, Sharp called for artillery fire as he moved to bring his exposed section back into line and then gradually draw his platoon into all-round defence.[134] He reported that he was under fire from a force estimated to be platoon-sized.[135] The Australians started the contact believing they were the numerically superior force and would attack the Viet Cong, yet far from clashing with a small force which would attempt to withdraw before being decisively engaged, 11 Platoon had run into the forward troops of a main force regiment.[134] Beginning as an encounter battle, heavy fighting ensued as the advancing battalions of the 275th Regiment and D445 Battalion clashed with D Company, 6 RAR and attempted to encircle and destroy them.[87]

11 Platoon is isolated

Amid the noise of machine-gun and rifle fire and the Viet Cong bugle calls, Stanley quickly brought the 161st Battery, Royal New Zealand Artillery into action in an attempt to support the Australian infantry. Yet as he was unable to see them, for safety reasons the initial rounds were directed a distance from 11 Platoon's known location, before "walking" the fire in to between 200 to 300 metres (220 to 330 yd) from their position, aided by D Company's favourable location between the Viet Cong and the gun position at Nui Dat, which allowed the rounds to pass over their heads and fall away from them.[118] Falling beyond 11 Platoon, the rounds exploded amid the Viet Cong as they began to form up for an assault.[136] But with 11 Platoon engaged from its left, front and right, it became clear the Viet Cong force was stronger than a platoon, and was probably at least company-sized. Supported by heavy machine-guns, they launched a series of assaults against 11 Platoon, only to be held off by small arms and artillery fire.[137] As the fighting continued Stanley realised that a single artillery battery would be insufficient, and at 16:19 he requested a regimental fire mission, using all 24 guns of the 1st Field Regiment, RAA. The Viet Cong continued their assault regardless, surging around the flanks of 11 Platoon. The Australians responded with controlled small arms fire, picking off a number of Viet Cong soldiers as the rain and artillery continued to fall around them. After making the required corrections Stanley requested another regimental fire mission at 16:22, yet still unable to see the rounds land he had to work entirely from radio communications with 11 Platoon, adjusting the fire over an area of 200 metres (220 yd) using just a map.[138]

New Zealand gunners carry out a fire mission.

Less than twenty minutes after the initial contact more than a third of 11 Platoon had been killed or wounded.[133] Several 60 mm light mortar rounds were subsequently fired towards the D Company position and although they landed to the east they further separated the remainder of the company from 11 Platoon, putting the main body behind a slight rise. At 16:26 Smith reported to Townsend that D Company was facing a force of company-size and that they were using mortars, urgently called for artillery support. Shortly afterwards Sharp was shot and killed after he raised himself to observe the fall of shot. With the platoon commander dead, Buick took charge of 11 Platoon, directing the artillery through Stanley. Unable to extricate itself, 11 Platoon was almost surrounded as the Viet Cong continued to assault their position. Suffering heavy casualties and running short of ammunition, Buick desperately radioed for assistance. Soon after the aerial of the platoon's radio was shot away and communications were lost. Meanwhile, Smith requested aerial fire support from armed CH-47 Chinooks or an air-strike to deal with the mortars.[134] In response, Stanley organised counter-battery fire from the American 155 mm self-propelled howitzers at Nui Dat, which appeared to silence them.[139] These mortars were not the 82 mm variants that had bombarded Nui Dat on 16/17 August and although no further mortar fire was reported at the time, they may have fired at B Company later in the battle.[140][141]

Meanwhile, 10 Platoon was approximately 200 metres (220 yd) to the north and Smith ordered it to move up on the left of 11 Platoon to try to relieve pressure on them and allow a withdrawal back to the company defensive position. Dropping their packs, Kendall's platoon wheeled to the south-east in extended line, advancing towards 11 Platoon. As they came over a small rise, through the rain they observed a regular Viet Cong platoon of 30 to 40 men advancing south, firing on 11 Platoon as they attempted to outflank them.[134] Advancing to close range before dropping to their knees to adopt firing positions, 10 Platoon engaged them from the rear, hitting a large number and breaking up the attack.[134][142] As the surviving Viet Cong withdrew, Kendall pushed on. Yet shortly after 10 Platoon was also heavily engaged on three sides from a heavy machine-gun firing tracer from the high ground of the Nui Dat 2 feature 400 metres (440 yd) to their left, wounding the signaller and damaging the radio and putting it out of action.[143][144] Now also without communications, and still 100 to 150 metres (110 to 160 yd) from 11 Platoon, 10 Platoon moved into a defensive position, fighting hard to hold on. Finally a runner arrived from Company Headquarters with a replacement radio, having moved 200 to 300 metres (220 to 330 yd) through heavy fire as he attempted to locate the platoon, killing two Viet Cong with his Owen gun on the way. With the wounded starting to arrive back at Smith's position and communications with 10 Platoon restored, he ordered Kendall to pull back under cover of the artillery.[134] 10 Platoon was ultimately forced back to its start point.[145]

Reaction at Nui Dat

It appeared the Viet Cong would shortly overrun D Company if they were not soon reinforced. Yet, with 1 ATF lacking sufficient forces to maintain a dedicated reserve at Nui Dat, no suitable quick reaction force was prepared to deploy at short notice. Consequently it would take several hours to organise a relief force.[146] Although essentially a sub-unit battle fought by a rifle company supported by artillery and co-ordinated by Townsend from the 6 RAR command post at Nui Dat, Jackson was concerned. Not only was D Company in trouble, but the entire force might be under threat, while the additional resources available to the task force might be required. As a result he remained in constant contact with Townsend, although ultimate control remained with the latter.[147] Viet Cong jamming on the Battalion Command net forced them to switch frequencies to communicate with D Company, while with such a capability rarely found below divisional-level, they were likely more heavily outnumbered than first thought.[148] At 16:30 Townsend issued a warning order to A Company to prepare to reinforce them, despite themselves only having returned from a three-day patrol an hour prior. Intending to lead the company out himself and take command of the battle, 3 Troop, 1st APC Squadron under Lieutenant Adrian Roberts was also warned to be ready to lift the relief force. American ground attack aircraft at Bien Hoa were also placed on alert by Headquarters 1 ATF. Meanwhile, on hearing the sounds of the fighting while returning to Nui Dat, B Company halted 2,300 metres (2,500 yd) short of the base and was ordered to rejoin D Company. Apparently under close observation from the Viet Cong, they were engaged by two 60 mm mortars as they turned around, but suffered no casualties.[149]

Requiring the task force commander's permission to send out the relief force and to accompany it, Townsend telephoned Jackson. Jackson was concerned for the safety of the entire force and was initially reluctant to authorise the dispatch of the relief force should it weaken the position at Nui Dat. He was unsure of the size of the Viet Cong facing D Company, although from Smith's reports it appeared to be at least a regular battalion. Meanwhile, intelligence suggested it was likely part of the 275th Regiment, although the locations of the remaining two battalions of the regiment were unknown, as were those of D445 Battalion.[150] The location of the 274th Regiment was equally unclear. Although radio direction finding suggested it may have been near Phuoc Tuy's northern border, three weeks earlier it had been reported close to the western side of the Australian TAOR, while one of its battalions had incorrectly been believed to be involved in an attack on Phu My in the south-west of the province on 11 August.[150][151] Consequently, Jackson reasoned that if the battle unfolding near Long Tan was the opening phase of an attack on Nui Dat the main assault was still to come, and he would require the bulk of his forces to defend the task force base. He considered the commitment of A Company would tie up the bulk of 6 RAR and the artillery. Yet Townsend believed Nui Dat's defences to be sufficient to deter such an attack, even if they remained incomplete, while the strategic reserve held by US II FFV could also be enacted if required. Ultimately Jackson gave his in-principle support to the plan; however, he would not release the relief force until he thought it warranted.[150]

Fighting continues

By 16:50 it was apparent to Smith that he was facing a force of at least battalion-strength. Yet with his two forward platoons still separated and unable to support each other, D Company was badly positioned for a defensive battle. 10 Platoon had been prevented from engaging the Viet Cong attacking 11 Platoon, and was unable to support its withdrawal as a result. Meanwhile, 11 Platoon had gone to ground in extended line following the initial contact, leaving its flanks vulnerable, while its aggressive push forward prior to the engagement also complicated the application of artillery support, which had to be switched to support each platoon as required rather than allowing it to be concentrated. Unable to see either platoon, the D Company artillery forward observer was unsure of 11 Platoon's exact position, further delaying the process.[152] As a consequence 10 and 11 Platoons were each forced to fight their own battles, and despite the weight of the indirect fire increasingly becoming available to support the Australian infantry, the Viet Cong were able to apply superior fire power as they tried to isolate and attack each platoon in turn. To retrieve the situation Smith planned to pull his company into an all-round defensive position to enable his platoons to support each other and fight a co-ordinated battle and care for the wounded until a relief force could arrive to assist.[152] Seemingly intent on attacking Nui Dat, the Viet Cong moved to overrun the beleaguered force, but the dispersal of the Australian platoons made it difficult for them to find D Company's flanks and roll them up, and may have led the Viet Cong commander to assess that he was facing a much larger Australian force.[153]

US F-4 Phantoms over South Vietnam.

In the meantime Buick succeeded in repairing the 11 Platoon radio, and was able to re-establish communications with Company Headquarters, and with Stanley, who was again able to adjust the artillery by radio.[154][152] Yet the Viet Cong succeeded in closing to within 50 metres (55 yd) of 11 Platoon's position, and much of the artillery was beginning to fall behind them as a result. Although the fire was likely impacting the Viet Cong rear area and was probably causing considerable casualties there, the assault troops had deliberately closed with the Australians to negate its effect. Buick estimated 11 Platoon was being assaulted by at least two companies; down to the last of their ammunition and with just 10 of its 28 men still able to fight, he feared the platoon would soon be overrun and destroyed, and would be unlikely to survive more than the next 10 to 15 minutes.[155] Confident the rest of D Company would be attempting to reach them, but unable to see how that might occur, Buick requested artillery fire onto his own position despite the danger this entailed. Stanley refused, although after confirming 11 Platoon's precarious situation, he was able to walk the artillery in closer. Landing 50 to 100 metres (160 to 330 ft) to their front, the artillery detonated among a large concentration of Viet Cong troops, destroying an entire assault line as they formed up.[147][156] Three US F-4 Phantoms arrived on station at 17:00 for an airstrike arranged by Battalion Headquarters.[157]

At 17:02 Smith reported D Company was running low on ammunition and required aerial resupply. With just three magazines carried by each rifleman, the Australians were only lightly equipped prior to the battle. This was a standard load calculated on 1 RAR usage rates which had been enough during previous actions, but it proved insufficient for sustained fighting. Due to the thick vegetation the ammunition boxes would need to be dropped through the trees, and intending on moving his headquarters behind a low knoll, Smith nominated a point 400 metres (440 yd) west. This position would afford greater protection, while the helicopters would be less likely to attract ground fire. Yet with their casualties now unable to be moved, D Company would have to remain in location instead.[150] Townsend passed the ammunition demand to Headquarters 1 ATF. In response Jackson requested two UH-1B Iroquois from No. 9 Squadron RAAF to deliver it; however, the senior Air Force officer at Nui Dat, Group Captain Peter Raw, was not prepared to risk aircraft hovering at tree-top height in the heavy rain where they would be exposed to ground fire, citing Department of Air regulations. Relations between the Army and Air Force over the use of the helicopters had become increasingly bitter in the months prior, and were still tenuous despite recent improvements. Jackson requested American assistance, and when the US Army liaison officer responded more favourably, Raw felt no alternative than to accede to the original request, offering RAAF helicopters to effect the resupply instead.[158] By coincidence two Iroquois were available at Nui Dat, having been used as transport for the concert and were committed to support D Company.[159]

Smith requested close air support, calling for the waiting aircraft to drop napalm across 11 Platoon's eastern frontage. The Phantoms were soon overhead; however, due to the rain and low cloud they were unable to observe the coloured smoke thrown by the Australians to mark their position through the trees. Stanley was forced to halt the artillery while the aircraft flew overhead, yet with Smith unable to establish communications with the forward air observer he wanted them out of the area so it could resume firing. Townsend directed the aircraft to drop their payloads on the forward slopes of the Nui Dat 2 feature instead, believing it the location of the Viet Cong command element.[160] With the artillery beginning to fall again and with the Australians still heavily outnumbered it proved critical in preventing them from being overrun as the Viet Cong formed assault waves. Major Harry Honnor—officer commanding 161st Battery, RNZA which was attached to 6 RAR as its direct support battery—served as artillery advisor to Townsend at Nui Dat and during the battle controlled the fires of the three field batteries, as well as directing the American medium artillery against depth targets. On the ground Stanley would either call down the fire himself or would relay the direction of the assault by radio, from which Honnor would select targets and order the fire, which was then adjusted by Stanley using sound ranging to bring it closer. Despite the rain and the soft ground reducing the impact of the shell bursts, the effectiveness of the artillery was aided by the otherwise favourable technical conditions, including the location of the infantry between the guns and the assaulting Viet Cong, the convenient range of 5,000 to 6,000 metres (5,500 to 6,600 yd) at which the engagement occurred, good communications afforded by the newly issued PRC-25 radios, the air burst effect created by rounds exploding in the rubber trees, and a large supply of rounds which had been stock-piled at Nui Dat.[161]

12 Platoon attempts to link up with Buick

Having been repulsed on the left, Smith tried the right flank. Pushing his headquarters forward, he ordered Sabben to move 12 Platoon—until then held in reserve—up on the right to support 11 Platoon.[145] Yet as new radio traffic was received Smith was again forced to ground to work on fresh orders, while the arrival of an increasing number of casualties required the establishment of an aid post in the dead ground, which effectively tied them in location and prevented further manoeuvre.[147] Meanwhile, at 17:05 Roberts arrived at the 6 RAR headquarters at Nui Dat with his troop of 10 APCs, and was quickly briefed by the Operations Officer on the situation before departing to pick up A Company from their lines.[162] After more than an hour of fighting D Company was still widely dispersed; 10 Platoon had been unable to break through to 11 Platoon from the north, while there remained only a slight chance 12 Platoon would have more success from the north-west. With the Viet Cong enjoying a considerable numerical advantage Smith feared his platoons would be defeated in detail and that it was only a matter of time before his entire company would be overrun, despite the devastating effect of the artillery on the Viet Cong assault formations.[163] 12 Platoon stepped off at 17:15, moving south-east in an attempt to retrieve the now cut-off 11 Platoon, but having been forced to leave 9 Section behind to protect Company Headquarters and support the wounded, with just two sections it was significantly under-strength.[147]

At 17:20 Smith requested an airmobile assault to reinforce his position; however, due to the bad weather, poor visibility, time of day and lack of a suitable landing zone this was considered impossible. Instead, Townsend informed him a relief force consisting of an infantry company mounted in APCs would be dispatched.[164] Yet Jackson was reluctant to reduce the defences at Nui Dat, considering the attack a possible feint. Consequently, although Smith had repeatedly pressed Townsend there had been a delay of more than an hour from when the relief force was ordered to ready themselves to the time Roberts was allowed to move.[165][Note 3] Townsend finally ordered the relief force to move at 17:30, having received Jackson's approval for their release. A Company, 6 RAR and 3 APC Troop had been on standby in the company lines and departed fifteen minutes later. But with the route largely dictated by the terrain, the possibility of the relief force being ambushed concerned Townsend and Jackson. Regardless, neither saw any alternative given the dire situation and considered it unlikely given the ground had been covered by frequent patrols, the proximity of D Company's position to Nui Dat, the open country between the base and the rubber plantation and the fact it was still daylight, even if the light was rapidly fading. With 5 RAR back at Nui Dat, Jackson ordered it to take over the defensive positions normally occupied by 6 RAR, while deploying a platoon to the 1st APC Squadron lines, and placing D Company, 5 RAR on one hour's notice to move if required.[164] The remainder of the battalion prepared to repel any attack on Nui Dat or to pursue the Viet Cong if they withdrew.[112]

No. 9 Squadron RAAF Iroquois in Vietnam.