| Buffalo Soldiers | |

|---|---|

Buffalo Soldiers of the 25th Infantry Regiment in 1890 | |

| Active | 1866–1951 |

| Country |

|

| Branch | U.S. Army |

| Nickname(s) | "Buffalo Soldiers" |

| Engagements |

American Indian Wars Banana Wars Spanish-American War Philippine-American War Border War World War I World War II |

Buffalo Soldiers originally were members of the U.S. 10th Cavalry Regiment of the United States Army, formed on September 21, 1866 at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. This nickname was given to the "Negro Cavalry" by the Native American tribes they fought; the term eventually became synonymous with all of the African-American regiments formed in 1866:

Although several African-American regiments were raised during the Civil War as part of the Union Army (including the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry and the many United States Colored Troops Regiments), the "Buffalo Soldiers" were established by Congress as the first peacetime all-black regiments in the regular U.S. Army.[1] On September 6, 2005, Mark Matthews, who was the oldest living Buffalo Soldier, died at the age of 111. He was buried at Arlington National Cemetery.[2]

Etymology[]

Sources disagree on how the nickname "Buffalo Soldiers" began. According to the Buffalo Soldiers National Museum, the name originated with the Cheyenne warriors in the winter of 1877, the actual Cheyenne translation being "Wild Buffalo." However, writer Walter Hill documented the account of Colonel Benjamin Grierson, who founded the 10th Cavalry regiment, recalling an 1871 campaign against Comanches. Hill attributed the origin of the name to the Comanche due to Grierson's assertions. The Apache used the same term, "We called them 'buffalo soldiers,' because they had curly, kinky hair...like bisons."[3] Some sources assert that the nickname was given out of respect for the fierce fighting ability of the 10th Cavalry.[4] Other sources assert that Native Americans called the black cavalry troops "buffalo soldiers" because of their dark curly hair, which resembled a buffalo's coat.[5] Still other sources point to a combination of both legends.[6] The term Buffalo Soldiers became a generic term for all African-American soldiers. It is now used for U.S. Army units that trace their direct lineage back to the 9th and 10th Cavalry units whose service earned them an honored place in U.S. history.

In September 1867, Private John Randall of Troop G of the 10th Cavalry Regiment was assigned to escort two civilians on a hunting trip. The hunters suddenly became the hunted when a band of 70 Cheyenne warriors swept down on them. The two civilians quickly fell in the initial attack and Randall's horse was shot out from beneath him. Randall managed to scramble to safety behind a washout under the railroad tracks, where he fended off the attack with only his pistol until help from the nearby camp arrived. The Cheyenne beat a hasty retreat, leaving behind 13 fallen warriors. Private Randall suffered a gunshot wound to his shoulder and 11 lance wounds, but recovered. The Cheyenne quickly spread word of this new type of soldier, "who had fought like a cornered buffalo; who like a buffalo had suffered wound after wound, yet had not died; and who like a buffalo had a thick and shaggy mane of hair."[7][8]

Service[]

During the American Civil War, the U.S. government formed regiments known as the United States Colored Troops, composed of black soldiers. After the war, Congress reorganized the Army and authorized the formation of two regiments of black cavalry with the designations 9th and 10th U.S. Cavalry, and four regiments of black infantry, designated the 38th, 39th, 40th and 41st Infantry Regiments (Colored). The 38th and 41st were reorganized as the 25th Infantry Regiment, with headquarters in Jackson Barracks in New Orleans, Louisiana, in November 1869. The 39th and 40th were reorganized as the 24th Infantry Regiment, with headquarters at Fort Clark, Texas, in April 1869. All of these units were composed of black enlisted men commanded by both white and black officers. These included the first commander of the 10th Cavalry Benjamin Grierson, the first commander of the 9th Cavalry Edward Hatch, Medal of Honor recipient Louis H. Carpenter, the unforgettable Nicholas M. Nolan, and the first black graduate of West Point, Henry O. Flipper.

History[]

Indian Wars[]

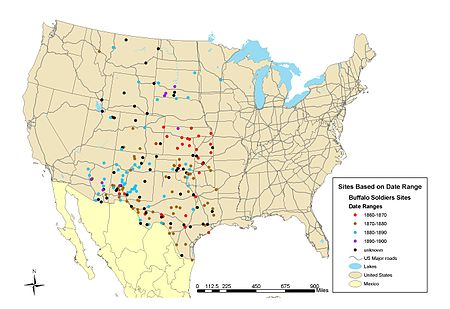

From 1866 to the early 1890s, these regiments served at a variety of posts in the Southwestern United States and the Great Plains regions. They participated in most of the military campaigns in these areas and earned a distinguished record. Thirteen enlisted men and six officers from these four regiments earned the Medal of Honor during the Indian Wars. In addition to the military campaigns, the "Buffalo Soldiers" served a variety of roles along the frontier from building roads to escorting the U.S. mail. On April 17, 1875, regimental headquarters for the 9th and 10th Cavalries were transferred to Fort Concho, Texas. Companies actually arrived at Fort Concho in May 1873. At various times from 1873 through 1885, Fort Concho housed 9th Cavalry companies A–F, K, and M, 10th Cavalry companies A, D–G, I, L, and M, 24th Infantry companies D–G, and K, and 25th Infantry companies G and K.[9]

Buffalo Soldier in the 9th Cavalry, 1890

A lesser known action was the 9th Cavalry's participation in the fabled Johnson County War, an 1892 land war in Johnson County, Wyoming between small farmers and large, wealthy ranchers. It culminated in a lengthy shootout between local farmers, a band of hired killers, and a Posse comitatus. The 6th Cavalry was ordered in by President Benjamin Harrison to quell the violence and capture the band of hired killers. Soon afterward, however, the 9th Cavalry was specifically called on to replace the 6th. The 6th Cavalry was swaying under the local political and social pressures and was unable to keep the peace in the tense environment.

The Buffalo Soldiers responded within about two weeks from Nebraska, and moved the men to the rail town of Suggs,Wyoming, creating "Camp Bettens" despite a racist and hostile local population. One soldier was killed and two wounded in gun battles with locals. Nevertheless, the 9th Cavalry remained in Wyoming for nearly a year to quell tensions in the area.[10][11]

1898–1918[]

Buffalo Soldiers who participated in the Spanish American War

After most of the Indian Wars ended in the 1890s, the regiments continued to serve and participated in the 1898 Spanish-American War (including the Battle of San Juan Hill) in Cuba, where five more Medals of Honor were earned.[12][13]

The men of the Buffalo soldiers were only some of the 5,000 Black men who served in the Spanish-American war.[14]

The regiments took part in the Philippine-American War from 1899 to 1903 and the 1916 Mexican Expedition.[12][13]

In 1918 the 10th Cavalry fought at the Battle of Ambos Nogales during the First World War, where they assisted in forcing the surrender of the federal Mexican and Mexican militia forces.[12][13][15]

Buffalo soldiers fought in the last engagement of the Indian Wars; the small Battle of Bear Valley in southern Arizona which occurred in 1918 between U.S. cavalry and Yaqui natives.[12][13]

Park Rangers[]

Another little-known contribution of the Buffalo Soldiers involved eight troops of the 9th Cavalry Regiment and one company of the 24th Infantry Regiment who served in California's Sierra Nevada as some of the first national park rangers. In 1899, Buffalo Soldiers from Company H, 24th Infantry Regiment briefly served in Yosemite National Park, Sequoia National Park and General Grant (Kings Canyon) National Parks.[16]

U.S. Army regiments had been serving in these national parks since 1891, but until 1899 the soldiers serving were white. Beginning in 1899, and continuing in 1903 and 1904, African-American regiments served during the summer months in the second and third oldest national parks in the United States (Sequoia and Yosemite). Because these soldiers served before the National Park Service was created (1916), they were "park rangers" before the term was coined.

A lasting legacy of the soldiers as park rangers is the Ranger Hat (popularly known as the Smokey Bear Hat). Although not officially adopted by the Army until 1911, the distinctive hat crease, called a Montana Peak, (or pinch) can be seen being worn by several of the Buffalo Soldiers in park photographs dating back to 1899. Soldiers serving in the Spanish American War began to recrease the Stetson hat with a Montana "pinch" to better shed water from the torrential tropical rains. Many retained that distinctive "pinch" upon their return to the U.S. The park photographs, in all likelihood, show Buffalo Soldiers who were veterans from that 1898 war.

One particular Buffalo Soldier stands out in history: Captain Charles Young who served with Troop "I", 9th Cavalry Regiment in Sequoia National Park during the summer of 1903. Charles Young was the third African American to graduate from the United States Military Academy. At the time of his death, he was the highest ranking African American in the U.S. military. He made history in Sequoia National Park in 1903 by becoming Acting Military Superintendent of Sequoia and General Grant National Parks. Charles Young was also the first African American superintendent of a national park. During Young's tenure in the park, he named a Giant Sequoia for Booker T. Washington. Recently, another Giant Sequoia in Giant Forest was named in Captain Young's honor. Some of Young's descendants were in attendance at the ceremony.[17]

Buffalo Soldiers National Museum in Houston, Texas

Entrance to Buffalo Soldiers National Museum in Houston, Texas

In 1903, 9th Cavalrymen in Sequoia built the first trail to the top of Mount Whitney, the highest mountain in the contiguous United States. They also built the first wagon road into Sequoia's Giant Forest, the most famous grove of Giant Sequoia trees in Sequoia National Park.

In 1904, 9th Cavalrymen in Yosemite built an arboretum on the South Fork of the Merced River in the southern section of Yosemite National Park. This arboretum had pathways and benches, and some plants were identified in both English and Latin. Yosemite's arboretum is considered to be the first museum in the National Park System. The NPS cites a 1904 report, where Yosemite superintentent (Lt. Col.) John Bigelow, Jr. declared the arboretum "To provide a great museum of nature for the general public free of cost ..." Unfortunately, the forces of developers, miners and greed cut the boundaries of Yosemite in 1905 and the arboretum was nearly destroyed.[18]

In the Sierra Nevada, the Buffalo Soldiers regularly endured long days in the saddle, slim rations, racism, and separation from family and friends. As military stewards, the African-American cavalry and infantry regiments protected the national parks from illegal grazing, poaching, timber thieves, and forest fires. Yosemite Park Ranger Shelton Johnson researched and interpreted the history in an attempt to recover and celebrate the contributions of the Buffalo Soldiers of the Sierra Nevada.[19]

In total, 23 "Buffalo Soldiers" received the Medal of Honor during the Indian Wars.[20]

West Point[]

On March 23, 1907, the United States Military Academy Detachment of Cavalry was changed to a "colored" unit. This had been a long time coming. It had been proposed in 1897 at the "Cavalry and Light Artillery School" at Fort Riley, Kansas that West Point Cadets learn their riding skills from the black non-commissioned officers who were considered the best. The one hundred man detachment from the 9th Cavalry served to teach future officers at West Point riding instruction, mounted drill and tactics until 1947.[21]

Systemic prejudice[]

The "Buffalo Soldiers" were often confronted with racial prejudice from other members of the U.S. Army. Civilians in the areas where the soldiers were stationed occasionally reacted to them with violence. Buffalo Soldiers were attacked during racial disturbances in Rio Grande City, Texas in 1899,[22] Brownsville, Texas in 1906,[23] and Houston, Texas in 1917.[24][25]

Pershing[]

General of the Armies John J. Pershing is a controversial figure regarding the Buffalo Soldiers. He served with the 10th Cavalry from October 1895 to May 1897. He served again with them for less than six months in Cuba. Because he saw the "Buffalo Soldiers" as good soldiers, he was looked down upon and called "N***** Jack" by white cadets and officers at West Point. It was only later during the Spanish-American War that the press changed that insulting term to "Black Jack." [26] During World War I Pershing bowed to the racial policies of President of the United States Woodrow Wilson, Secretary of War Newton D. Baker and the southern Democratic Party with its "separate but equal" philosophy. For the first time in American history, Pershing allowed American soldiers (African-Americans) to be under the command of a foreign power.[n 1]

The Punitive Expedition, U.S.-Mexico Border, and World War I[]

The outbreak of the Mexican Revolution in 1910 against the long-time rule of President Porfirio Díaz initiated a decade-long period of high-intensity military conflict along the U.S.-Mexico border as different political/military factions in Mexico fought for power. The access to arms and customs duties from Mexican communities along the U.S.-Mexico boundary made border towns like Matamoros, Tamaulipas, Ojinaga, Chihuahua, and Nogales, Sonora, important strategic assets. As the various belligerents in Mexico vied for power, the U.S. Army, including the Buffalo Soldier units, was dispatched to the border to maintain security. The Buffalo Soldiers played a key role in U.S.-Mexico relations as the maelstrom that followed the ouster of Díaz and the assassination of his successor Francisco Madero intensified.[citation needed]

Buffalo Soldiers of the U.S. 10th Cavalry Regiment who were taken prisoner during the Battle of Carrizal, Chihuahua, Mexico in 1916.

By late 1915 the political faction led by Venustiano Carranza received diplomatic recognition from the U.S. government as the legitimate ruling force in Mexico. Francisco "Pancho" Villa, who had previously courted U.S. recognition and thus felt betrayed, then attacked the rural community of Columbus, New Mexico, directly leading to further border tensions as U.S. President Woodrow Wilson unilaterally dispatched the Punitive Expedition into Chihuahua, Mexico, under General John Pershing to apprehend or kill Villa. The 9th and 10th Cavalries were deployed to Mexico along with the rest of Pershing's units. Although the manhunt against Villa was unsuccessful, small-scale confrontations in the communities of Parral and Carrizal nearly brought about a war between Mexico and the United States in the summer of 1916. Tensions cooled through diplomacy as the captured Buffalo Soldiers from Carrizal were released. Despite the public outrage over Villa's Columbus raid, Wilson and his cabinet felt that the U.S.'s attention ought to be centered on Germany and World War I, not the apprehension of the "Centauro del Norte." The Punitive Expedition exited Mexico in early 1917, just before the U.S. declaration of war against Germany in April 1917.[citation needed]

The Buffalo Soldiers did not participate with the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) during World War I, but experienced non-commissioned officers were provided to other segregated Black units for combat service—such as the 317th Engineer Battalion. The Soldiers of the 92nd Infantry Division (United States) and the 93rd Infantry Division (United States) were the first Americans to fight in France. The four regiments of 93rd fought under French command for the duration of the war.

The U.S.-Mexico border in Nogales in 1898. International Street/Calle Internacional runs through the center of the image between Nogales, Sonora (left), and Nogales, Arizona (right). Note the wide open nature of the international boundary. A Customs House is located near the center of the image.

On August 27, 1918, the 10th Cavalry supported the 35th Infantry Regiment in a border skirmish in the border towns of Nogales, Arizona, and Nogales, Sonora, between U.S. military forces, Mexican Federal troops and armed Mexican civilians (militia) in the Battle of Ambos Nogales. This was the only documented incident in which German military advisors fought along with Mexican soldiers and the only battle during World War I where Germans engaged and died in combat against United States soldiers on North America soil.[13][15]

The 35th Infantry Regiment was stationed at Nogales, Arizona, on August 27, 1918, when at about 4:10 pm, a gun battle erupted unintentionally when a Mexican civilian attempted to pass through the border, back to Mexico, without being interrogated at the U.S. Customs house. After the initial shooting, reinforcements from both sides rushed to the border. On the Mexican side, the majority of the belligerents were angry civilians upset with the killings of Mexican border crossers by the U.S. Army along the vaguely-define border between the two cities during the previous year (the U.S. Border Patrol did not exist until 1924). For the Americans, the reinforcements were the 10th Cavalry, off-duty 35th Regimental soldiers and milita. Hostilities quickly escalated and several soldiers were killed and others wounded on both sides, including the mayor of Nogales, Sonora, Felix B. Peñaloza (killed when waving a white truce flag/handkerchief with his cane). A cease fire was arranged later after the US forces took the heights south of Nogales, Arizona.[13][15][27]

Due in part to the heightened hysteria caused by World War I, allegations surfaced that German agents fomented this violence and died fighting alongside the Mexican troops they led. U.S. newspaper reports in Nogales prior to the August 27, 1918 battle documented the departure of part of the Mexican garrison in Nogales, Sonora, to points south that August in an attempt to quell armed political rebels.[28][29][30]

Despite the Battle of Ambos Nogales controversy, the presence of the Buffalo Soldiers in the community left a significant impact on the border town. The famed jazz musician Charles Mingus was born in the Camp Stephen Little military base in Nogales in 1922, son to a Buffalo Soldier.[31] The African-American population, centered on the stationing of Buffalo Soldiers such as the 25th Infantry in Nogales, was a significant factor in the community, even though they often faced racial discrimination in the binational border community in addition to racial segregation at the elementary school level in Nogales's Grand Avenue/Frank Reed School (a school reserved for Black children).[32] The redeployment of the Buffalo Soldiers to other areas and the closure of Camp Little in 1933 initiated the decline of the African-American community in Nogales.

World War II[]

With colors flying and guidons down, the lead troops of the famous 9th Cavalry pass in review at the regiment's new home in rebuilt Camp Funston. Ft. Riley, Kansas, May 1941.

Prior to WW2, the black 25th Infantry Regt was based at Ft Huachuca Arizona. During the war, Ft Huachuca served as the home base of the Black 92nd and 93rd Infantry Divisions. The 9th and 10th Cavalry Regiments were essentially disbanded and the soldiers were moved into service-oriented units, along with the entire 2nd Cavalry Division. The 92nd Infantry Division, AKA the "Buffalo Division", served in combat during the Italian Campaign. The 93rd Infantry Division—including the 25th Infantry Regiment— served in the Pacific theater.[33] Separately, independent Black Artillery, Tank and Tank Destroyer Battalions as well as Quartermaster & support battalions served in WW2. All of these units to a degree carried on the traditions of the "Buffalo Soldiers".

Despite some official resistance and administrative barriers, black airmen were trained and played a part in the air war in Europe, gaining a reputation for skill and bravery (see Tuskegee Airmen). In early 1945, after the Battle of the Bulge, American forces in Europe experienced a shortage of combat troops so the embargo on using black soldiers in combat units was relaxed. The American Military History says:

Faced with a shortage of infantry replacements during the enemy's counteroffensive, General Eisenhower offered Negro soldiers in service units an opportunity to volunteer for duty with the infantry. More than 4,500 responded, many taking reductions in grade in order to meet specified requirements. The 6th Army Group formed these men into provisional companies, while the 12th Army Group employed them as an additional platoon in existing rifle companies. The excellent record established by these volunteers, particularly those serving as platoons, presaged major postwar changes in the traditional approach to employing Negro troops.

Korean War and integration[]

Buffalo Soldier Monument on Fort Leavenworth, Kansas

The 24th Infantry Regiment saw combat during the Korean War and was the last segregated regiment to engage in combat. The 24th was deactivated in 1951, and its soldiers were integrated into other units in Korea. On December 12, 1951, the last Buffalo Soldier units, the 27th Cavalry and the 28th (Horse) Cavalry, were disbanded. The 28th Cavalry was inactivated at Assi-Okba, Algeria in April 1944 in North Africa, and marked the end of the regiment.[34]

There are monuments to the Buffalo Soldiers in Kansas at Fort Leavenworth and Junction City.[35] Then-Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Colin Powell, who initiated the project to get a statue to honor the Buffalo Soldiers when he was posted as a brigadier general to Fort Leavenworth, was guest speaker for the unveiling of the Fort Leavenworth monument in July 1992.

Controversy[]

In the last decade, the employment of the Buffalo Soldiers by the United States Army in the Indian Wars has led a few alternate history historians to call for the "critical reappraisal" of the "Negro regiments." In this viewpoint, shared by a small minority,[36] the Buffalo Soldiers were used as mere shock troops or accessories to the forcefully-expansionist goals of the U.S. government at the expense of the Native Americans and other minorities.[36][37]

Legacy[]

Music[]

- The song and music of Soul Saga (Song of the Buffalo Soldier) has had several renditions. In 1974, it was produced by Quincy Jones in the album Body Heat.[38] In 1975, the album Symphonic Soul contained another variation and was released by Henry Mancini and his Orchestra.[39]

- The song "Buffalo Soldier", co-written by Bob Marley and King Sporty, first appeared on the 1983 album Confrontation. Many Jamaicans, especially Rastafarians like Marley, identified with the "Buffalo Soldiers" as an example of black men who performed with exceeding courage, honor, valor, and distinction in a field that was dominated by whites and persevered despite endemic racism and prejudice.[40]

- The song "Wavin' Flag" by Somalian/Canadian rapper K'naan from his album Troubadour includes the line "Cause we just move forward like Buffalo Soldiers." This song was produced by Kerry Brothers, Jr. (co-produced by Bruno Mars).[41] It was performed acoustically live on Q TV.[42]

- The song Buffalo Soldier by The Flamingos specifically refers to the 10th Cavalry Regiment. The song was a minor hit in 1970.[43] A cappella group The Persuasions remade the song on their album Street Corner Symphony This version was produced by David Dashev and Eric Malamud.[44][45]

- The song "Went for a Ride" by Radney Foster, specifically in the spoken introduction, tells the fictional story of a slave turned buffalo soldier and his life as a cowboy.[citation needed]

Media[]

Buffalo Soldier Memorial of El Paso, in Fort Bliss, depicting CPL John Ross, I Troop, 9th Cavalry, during an encounter in the Guadalupe Mountains during the Indian Wars

- The 1960 Western film Sergeant Rutledge, starring Woody Strode, tells the story of the trial of a 19th-century black Army non-commissioned officer falsely accused of rape and murder. One of the characters narrates the history of the term "buffalo soldier". The movie's theme song, titled Captain Buffalo, was written by Mack David and Jerry Livingston.[46]

- TV series: Incident of the Buffalo Soldier, Season 3, Episode 10, aired Jan 6, 1961. A Buffalo soldier is falsely accused of murder when it was self-defense. When a Rawhide regular is wounded the accused Buffalo Soldier brings him to safety but is killed under a shoot on sight order.[47]

- TV series: Incident at Seven Fingers, Season 6, Episode 30, Aired May 7, 1964. A top sergeant of Troop F, 110th Cavalry Regiment is accused of being a coward and a deserter. Other Buffalo Soldiers and an officer track him down. The Rawhide trail boss figures out that the sergeant is trying to protect the honor of his Captain who is suffering blackouts from a previous head wound. Honor and respect is restored.[47]

- On November 22, 1968, an episode of the television series The High Chaparral titled "The Buffalo Soldiers", starring Yaphet Kotto, paid tribute to the soldier's patriotic spirit.

- The 1970 television film Carter's Army (also known as the Black Brigade), starring Stephen Boyd, Rosey Grier and Richard Pryor, depicted a black unit during World War II, led by a white officer.

- The 1979 television film Buffalo Soldiers, starring Stan Shaw and John Beck, depicted African-American cavalry soldiers and their actions in the West during the Indian Wars of the late 19th century.

- The 1997 television film Buffalo Soldiers, starring Danny Glover, drew attention to their role in the military history of the United States.

- The 2006 History Channel special "Honor Deferred" describe members of the Buffalo soldiers in WWII Italy.

- The film Miracle at St. Anna, directed by Spike Lee, chronicles the Buffalo Soldiers who served in the invasion of Italy. It is based on the novel of the same name by James McBride.

Video games[]

- In the "wild west"-themed video games Red Dead Revolver (2004) and Red Dead Redemption (2010) by Rockstar Games, "Buffalo Soldier" is a name of a playable black character in a Union Army uniform.

Prominent members[]

- John Hanks Alexander

- Allen Allensworth

- Thomas Boyne, Medal of Honor recipient

- John Denny, Medal of Honor recipient

- Henry Ossian Flipper

- George B. Jackson

- Henry Johnson, Medal of Honor recipient

- Henry Parker

- Charles Young

See also[]

- Battle of the Saline River - one of the first combats of the 10th.

- Black Seminoles (Cimarrones)

- List of African American Medal of Honor recipients

- Military history of African Americans

- Camp Lockett

- Buffalo Soldier tragedy of 1877 also known as the "Staked Plains Horror."

- "Colonel" Charles Long

- The Buffalo Saga: Memoirs of James Harden Daugherty, who served with the 92nd Infantry during World War II.

- Tuskegee Airmen

- 1st Louisiana Native Guard

- 2nd Cavalry Division

- 92nd Infantry Division

- 93rd Infantry Division

- 366th Infantry Regiment

- 761st Tank Battalion

- 784th Tank Battalion

- MV Buffalo Soldier, a military sealift command maritime prepositioning ship named in honor of African-American regiments

- Tangipahoa African American Heritage Museum & Black Veteran Archives

Notes[]

- ↑ Pershing was a first lieutenant and took command of a troop of the 10th Cavalry Regiment in October 1895. In 1897, Pershing became an instructor at West Point, where he joined the tactical staff. While at West Point, cadets upset over Pershing's harsh treatment and high standards took to calling him "N***** Jack," in reference to his service with the 10th Cavalry.1 This was softened (or sanitized) to the more euphonic "Black Jack" by reporters covering Pershing during World War I.2 At the start of the Spanish-American War, First Lieutenant Pershing was offered a brevet rank and commissioned a major of volunteers on August 26, 1898. He fought with the 10th Cavalry (Buffalo Soldiers) on Kettle and San Juan Hill in Cuba and was cited for gallantry. During World War I General Pershing exercised significant control over the American Expeditionary Force. He had a full delegation of authority from President of the United States Woodrow Wilson and Secretary of War Newton D. Baker. Baker, cognizant of the endless problems of domestic and allied political involvement in military decision making in wartime, gave Pershing unmatched authority to run his command as he saw fit. In turn, Pershing exercised his prerogative carefully, not engaging in issues that might distract or diminish his command. While earlier a champion of the African-American soldier, he did not champion their full participation on the battlefield, bowing to widespread racial attitudes among white Americans, plus Wilson's reactionary racial views and the political debts he owed to southern "separate but equal" Democratic law makers.3

References[]

- ↑ Chap. CCXCIX. 14 Stat. 332 from "A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U. S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774 - 1875". Library of Congress, Law Library of Congress. Retrieved March 26, 2012.

- ↑ Shaughnessy, Larry (September 19, 2005). "Oldest Buffalo Soldier to be Buried at Arlington". CNN. http://www.cnn.com/2005/US/09/17/buffalo.soldier/index.html. Retrieved 2007-04-24.

- ↑ Lehmann, H., 1927, 9 Years Among the Indians, 1870-1879, Von Beockmann-Jones Company, p. 121

- ↑ "Brief History (Buffalo Soldiers National Museum)". 2008. http://www.nps.gov/goga/planyourvisit/upload/sb-buffalo-2008.pdf. Retrieved 2009-11-30.

- ↑ National Park Service. "Buffalo Soldiers" (PDF). Archived from the original on January 4, 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20070104024555/http://www.nps.gov/archive/goga/maps/bulletins/sb-buffalo.pdf. Retrieved 2007-05-01.

- ↑ The Smithsonian Institution. "The Price of Freedom: Printable Exhibition". http://americanhistory.si.edu/militaryhistory/printable/section.asp?id=6. Retrieved 2007-05-01.

- ↑ 7-10 Cav Global Security.org which references “ (Starr 1981:46).”

- ↑ "Official 4ID History 4th Infantry Division Homepage: History". United States Army. August 2, 2010. http://www.carson.army.mil/units/4id/units/unitsindex.html.

- ↑ "Fort Concho National Historic Landmark". San Angelo, TX: Fort Concho NHL. http://www.fortconcho.com/buffalo.htm. Retrieved January 2, 2009.

- ↑ Fields, Elizibeth Arnett. Historic Contexts for the American Military Experience

- ↑ Schubert, Frank N. "The Suggs Affray: The Black Cavalry in the Johnson County War". The Western Historical Quarterly, Vol. 4, No. 1 (January 1973), pp. 57–68.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 "10th Cavalry Squadron History". US Army. http://www.hood.army.mil/4id_1-10cavalrysquadron/sqdrnhist.htm.[dead link]

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 Finley, James P. Huachuca Illustrated Vol. 2 Part 5, Buffalo Soldiers at Huachuca: Yaqui Fight in Bear Valley. Library of Congress 1996, ISBN 93-206790 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Finely" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Clodfelter, Michael Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualties and Other Figures, 1494-2007

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Wharfield, Harold B., Colonel, USAF retired (1965). "Tenth Cavalry and Border Fights". El Cajon, CA: self published. pp. 85–97.

- ↑ Johnson, Shelton Invisible Men: Buffalo Soldiers of the Sierra Nevada. Park Histories: Sequoia NP (and Kings Canyon NP), National Parks Service. Retrieved: 2007-05-18.

- ↑ Leckie, William H. (1967). "The Buffalo Soldiers: A Narrative of the Negro Cavalry in the West". Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. LCCN 67-15571.

- ↑ Wallis, O. L. (September 1951). "Yosemite's Pioneer Arboreetum". Yosemite Nature Notes. Yosimite Natural History Association, Inc.. pp. 83. http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/yosemite_nature_notes/30/30-9.pdf. Retrieved 2010-05-05.

- ↑ Johnson, Shelton. "Shadows in the Range of Light". http://shadowsoldier.wilderness.net. Retrieved 2007-04-24.

- ↑ "Medal of Honor Recipients: Indian Wars Period". https://history.army.mil/html/moh/indianwars.html.

- ↑ Buckley, Gail Lumet, American Patriots: The Story of Blacks in the Military from the Revolution to Desert Storm, Random House; 1st edition (May 22, 2001).

- ↑ Christian, Garna (August 17, 2001). "Handbook of Texas Online: Rio Grande City, Texas". http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/view/RR/hfr5.html. Retrieved 2007-04-24.

- ↑ Christian, Garna (February 17, 2005). "Handbook of Texas Online: Brownsville, Texas". http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/pkb06. Retrieved 2007-04-24.

- ↑ Haynes, Robert (April 6, 2004). "Handbook of Texas Online: Houston, Texas". http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/jch04. Retrieved 2007-04-24.

- ↑ "The Officer Down Memorial Page (Police Officer Rufus E. Daniels)". http://www.odmp.org/officer.php?oid=3793. Retrieved 2007-04-24.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Frank E. Vandiver, Black Jack: The Life and Times of John J. Pershing – Volume I (Texas A&M University Press, Third printing, 1977) ISBN 0-89096-024-0 , 67.

- ↑ Clendenen, Clarence, Colonel (US Army retired) (1969). "Blood on the Border; the United States Army and the Mexican irregulars". New York: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-02-526110-5.

- ↑ General DeRosey C. Cabell, “Report on Recent Trouble at Nogales, 1 September 1918,” Battle of Nogales 1918 Collection, Pimeria Alta Historical Society (Nogales, AZ). See also DeRosey C. Cabell, “Memorandum for the Adjutant General: Subject: Copy of Records to be Furnished to the Secretary of the Treasury. 30 September 1918,” Battle of Nogales 1918 Collection, Pimeria Alta Historical Society (Nogales, AZ). Furthermore, an investigation by Army officials from Fort Huachuca, Arizona, could not substantiate accusations of militant German agents in the Mexican border community and instead traced the origins of the violence to the abuse of Mexican border crossers in the year prior to the Battle of Ambos Nogales. The main result of this battle was the building of the first permanent border fence between the two cities of Nogales.

- ↑ “Military Commanders Hold Final Conference Sunday,” Nogales Evening Daily Herald (Nogales, AZ), September 2, 1918; Daniel Arreola, “La Cerca y Las Garitas de Ambos Nogales: A Postcard Landscape Exploration,” Journal of the Southwest, vol. 43 (Winter 2001), pp. 504-541. Though largely unheard of in the U.S. (and even within most of Mexico), the municipal leaders of Nogales, Sonora, successfully petitioned the Mexican Congress in 1961 to grant the Mexican border city the title of "Heroic City", leading to the community's official name, Heroica Nogales, a distinction shared with other Mexican cities such as Heroica Huamantla, Tlaxcala, and Heroica Veracruz, Veracruz, communities that also saw military confrontation between Mexicans and U.S. military forces.

- ↑ Carlos F. Parra, "Valientes Nogalenses: The 1918 Battle Between the U.S. and Mexico That Transformed Ambos Nogales", Journal of Arizona History, Vol. 51 (Spring 2010), p. 26.

- ↑ "Charles Mingus Biography".

- ↑ Francisco Castro, "Overcoming Prejudice: Limitations Against Blacks in Nogales Did Not Stop Them from Accomplishments," In the Steps of Esteban, Tucson's African American Heritage.

- ↑ Hargrove, Hondon B. (1985). "Buffalo Soldiers in Italy: Black Americans in World War II". Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company. ISBN 0-89950-116-8.

- ↑ "The 28th Cavalry: The U.S. Army's Last Horse Cavalry Regiment". http://www.buffalosoldiers-lawtonftsill.org/28-cav.htm. Retrieved 2007-04-24.

- ↑ "Services – Buffalo Soldier Monument". Archived from the original on June 27, 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20070627001955/http://garrison.leavenworth.army.mil/sites/about/Buffalo.asp. Retrieved 2007-04-24.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 "The shame of the Buffalo Soldiers". http://www.hartford-hwp.com/archives/45a/389.html. Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- ↑ "The Buffalo Soldier of the West and the Elimination of the Native American Race". http://debate.uvm.edu/dreadlibrary/mullin.html. Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- ↑ Soul Saga (Song of the Bufallo Soldier), Jones, Quincy, 1974, A&M. 1988, Album Body Heat. ASIN: B000W0248E

- ↑ Soul Saga (Song of the Bufallo Soldier), Mancini, Henry, 1975, RCA CPL1-0672 (Quadraphonic) album Symphonic Soul."

- ↑ Black Heretics, Black Prophets: Radical Political Intellectuals – Bogues, Anthony, Page 198, via Google books. Accessed 2008-06-28.

- ↑ "K'Naan feat. Chali 2na (of Jurassic 5), Chubb Rock, Damian Marley, Mos Def – 'Troubadour' (Audio CD) Detail – Underground Hip Hop – Store". Underground Hip Hop. http://www.undergroundhiphop.com/store/detail.asp?UPC=AM47802CD. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- ↑ 'Waving Flag' by K'naan on QTV youtube.com

- ↑ Whitburn, Joel (2000). Top Pop Singles 1955-1999. Menomonee Falls, WI: Record Research, Inc.. p. 227. ISBN 0-89820-140-3.

- ↑ Buffalo Soldier, The Persuasions, 1971, Capitol Records. 1993, Album Street Corner Symphony. ASIN: B0000008N7

- ↑ 'Buffalo Soldier' by The Persuasions on Discogs

- ↑ IMDb. Sergeant Rutledge: Soundtrack.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 tv.com See also: The Rawhide Trail. Retrieved June 13, 2012.

- ↑ http://www.nps.gov/pwso/honor/pershing.htm

- ↑ Bak, Richard, Editor. "The Rough Riders" by Theodore Roosevelt. Page 172. Taylor Publishing, 1997.

- ↑ Frank E. Vandiver, Black Jack: The Life and Times of John J. Pershing – Volume II (Texas A&M University Press, Third printing, 1977) ISBN 0-89096-024-0

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Buffalo soldiers. |

- Buffalo Soldiers at San Juan Hill

- Buffalo Soldier Monument – Fort Leavenworth, Kansas

- Buffalo Soldier National Museum

- Photograph Gallery of Buffalo Soldiers On the Eve of War (World War II) at the United States Army Center of Military History

- Buffalo Soldiers from the Handbook of Texas Online

- shadowsoldier.wilderness.net, a website devoted to remembering the contributions of the buffalo soldiers of the Sierra Nevada, by Park Ranger Shelton Johnson, Yosemite National Park

- A Path to Lunch Liberation Day and the Liberation of America, Buffalo Soldiers in Lunigiana and Versilia, Italy.

- ENGAGEMENTS by the BUFFALO SOLDIERS AND SEMINOLE-NEGRO INDIAN SCOUTS

- Buffalo Soldiers during WW2 Captain Merrel Moody instructs Privates Enichel Kennedy, Oscar Davis, B. D. Kroninger and Will Johnson of Infantry School Stables, on the proper way to clean a saddle. Date: July 25, 1941.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The original article can be found at Buffalo Soldier and the edit history here.