| German auxiliary cruiser Atlantis | |

|---|---|

Atlantis | |

| Career (Germany) | |

| Name: | Goldenfels |

| Owner: | DDG Hansa |

| Operator: | DDG Hansa |

| Port of registry: | Bremen |

| Builder: | Bremer Vulkan |

| Launched: | 1937 |

| Identification: |

Code Letters DOTP |

| Fate: | Requisitioned by Kriegsmarine, 1939 |

| Career (Germany) | |

| Operator: | Kriegsmarine |

| Builder: | DeSchiMAG |

| Yard number: | 2 |

| Commissioned: | 30 November 1939 |

| Renamed: | Atlantis, 1939 |

| Reclassified: | Auxiliary cruiser, 1939 |

| Nickname: |

HSK-2 Schiff 16 Raider-C |

| Fate: | Sunk, 22 November 1941, in the South Atlantic |

| General characteristics [1] | |

| Type: | Merchant raider |

| Tonnage: |

7,862 gross register tons (GRT) NRT 4,845 |

| Displacement: | 17,600 t (17,300 long tons) |

| Length: | 155 m (509 ft) |

| Beam: | 18.7 m (61 ft) |

| Draught: | 8.7 m (29 ft) |

| Installed power: | 7,600 hp (5,700 kW) |

| Propulsion: |

2 × 6-cylinder diesel engines 1 × shaft |

| Speed: | 17.5 knots (32.4 km/h; 20.1 mph) |

| Range: | 60,000 nmi (110,000 km; 69,000 mi) at 10 kn (12 mph; 19 km/h) |

| Endurance: | 250 days |

| Complement: | 349-351 |

| Armament: |

6 × 150 mm (5.9 in) guns 1 × 75 mm (3.0 in) gun 2 × twin 37 mm anti-aircraft guns 2 × twin 20 mm cannons 4 × 533 mm (21 in) torpedo tubes 92 × mines |

| Aircraft carried: | 2 × Heinkel He 114C |

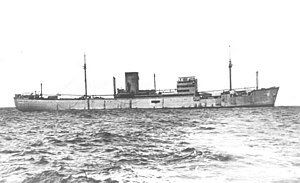

The German auxiliary cruiser Atlantis (HSK 2), known to the Kriegsmarine as Schiff 16 and to the Royal Navy as Raider-C, was a converted German Hilfskreuzer (auxiliary cruiser, or merchant or commerce raider) of the Kriegsmarine, which, in World War II, travelled more than 161,000 km (100,000 mi) in 602 days, and sank or captured 22 ships totaling 144,384 t (142,104 long tons). Atlantis was sunk on 22 November 1941 by the British cruiser HMS Devonshire (39).

She was commanded by Kapitän zur See Bernhard Rogge, who received the Oak Leaves to the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross.

Commerce raiders do not seek to engage warships, but rather attack enemy merchant shipping; the measures of success are tonnage destroyed (or captured) and time spent at large. Atlantis was second only to Pinguin in tonnage destroyed, and had the longest raiding career of any German commerce raider in either world war.

She had a significant effect on the war in the Far East due to her capture of highly significant secret documents from SS Automedon.

A version of the story of the Atlantis is told in the film, Under Ten Flags with Van Heflin appearing as Captain Rogge.

Early history[]

Built by Bremer Vulkan in 1937,[2] she began her career as the cargo ship Goldenfels, owned and operated by DDG Hansa, Bremen. Goldenfels was powered by two 12-cylinder Single Cycle Double Action diesel engines, built by Bremer Vulkan. She was allocated the Code Letters DOTP.[3] In late 1939 she was requisitioned by the Kriegsmarine and converted into a warship by DeSchiMAG, Bremen. In November 1939, she was commissioned as the commerce raider Atlantis.[2]:6–7

Design[]

Atlantis was 155 m (509 ft) long and displaced 17,600 t (17,300 long tons). She had a single funnel amidships. She had a crew of 349 (21 officers and 328 enlisted sailors) and a Scottish terrier, "Ferry", as a mascot. The cruiser carried a dummy funnel, variable-height masts, and was well supplied with paint, canvas, and materials for further altering her appearance, including costumes for the crew and flags. Atlantis was capable of being modified to twenty-six different silhouettes.

Weapons and aircraft[]

The ship was equipped with six 150 mm (5.9 in) guns, one 75 mm (3.0 in) gun on the bow, two twin-37 mm anti-aircraft guns and four 20 mm automatic cannons; all of these were hidden, mostly behind pivotable false deck or side structures. A phony crane and deckhouse on the aft section hid two of the 150 mm (5.9 in) guns; the other four guns were concealed via flaps in the side[4][5]:46 that were lowered when action was imminent. Atlantis also had four waterline torpedo tubes, and a 92-mine compartment. This gave her the fire power, and more importantly she possessed the fire control of a light cruiser. The ship also carried two Heinkel He-114C seaplanes in one of its holds, one of these was fully assembled and the other one was packed away in crates.[6]:8

Engines[]

Atlantis had two 6-cylinder diesel engines, which powered a single propeller. Top speed was 17.5 knots (32.4 km/h; 20.1 mph) and a range of 60,000 miles (97,000 km) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). Diesel engines allowed her to drift when convenient to conserve fuel, and unlike steam machinery, instantly restart her powerplant.

Service history[]

Journey to the South Atlantic[]

In 1939, she became the command of Kapitän Bernhard Rogge. Commissioned in mid-December, she was the first of nine or ten merchant ships armed by the Third Reich for the purposes of seeking out and engaging enemy cargo vessels. Atlantis was delayed by ice until 31 March 1940,[7] when the former battleship Hessen was sent to act as an icebreaker, clearing the way for Atlantis, Orion, and Widder.

Atlantis headed past the North Sea minefields, between Norway and Britain, across the Arctic Circle, between Iceland and Greenland, and headed south. By this time, Atlantis was pretending to be a Soviet vessel named Krim by flying the Soviet naval ensign, displaying a hammer and sickle on the bridge, and having Russian and English warnings on the stern, "Keep clear of propellers". The Soviet Union was neutral at the time.

After crossing the equator, on 24–25 April, she "became" the Japanese vessel Kasii Maru. The ship now displayed a large K upon a red-topped funnel, identification of the Kokusai Line. She also had rising sun symbols on the gun flaps and Japanese characters (copied from a magazine) on the aft hull.

City of Exeter[]

On 2 May, she met the British passenger liner SS City of Exeter. Rogge, unwilling to cause non-combatant casualties, declined to attack. Once the ships had parted, Exeter's Master radioed his suspicions about the "Japanese" ship to the Royal Navy.[8]

The Scientist[]

On 3 May, Atlantis met a British cargo ship, The Scientist, which was carrying ore and jute. The Germans raised their battle ensign and displayed signal pennants stating, "Stop or I fire! Don't use your radio!" The 75 mm (3.0 in) gun fired a warning shot. The British immediately began transmitting their alarm signal, "QQQQ...QQQQ...Unidentified merchantman has ordered me to stop," and the Germans began transmitting so as to jam the signals.

The Scientist turned to flee, but on the second salvo from Atlantis flames exploded from the ship, followed by a cloud of dust and then white steam from the boilers. A British sailor was killed and the remaining 77 were taken as prisoners of war. After failing to sink the ship with demolition charges, Atlantis used guns and a torpedo to finish off The Scientist.

Cape Agulhas[]

Continuing to sail south, Atlantis passed the Cape of Good Hope, reaching Cape Agulhas on 10 May. Here she set up a minefield with 92 horned contact naval mines, in a way which suggested that a U-boat had laid them. The minefield was successful, but the deception was foiled and the ship's presence revealed by a German propaganda broadcast boasting that "a minefield, sown by a German raider" had sunk no fewer than eight merchant ships, three more were overdue, three minesweepers were involved, and the Royal Navy was not capable of finding "a solitary raider" operating in "its own back yard". Furthermore a British signal was sent from Ceylon on 20 May and intercepted by Germany, based on the report from City of Exeter, warning shipping of a German raider disguised as a Japanese ship.[8]

Atlantis headed into the Indian Ocean disguised as the Dutch vessel MV Abbekerk. She received a broadcast—which happened to be incorrect—reporting that Abbekerk had been sunk, but retained that identity rather than repainting, as there were several similar Dutch vessels.[8]

Tirranna, City of Baghdad, and the Kemmendine[]

On 10 June 1940, Atlantis stopped the Norwegian motor ship Tirranna with 30 salvos of fire after a three-hour chase.[2]:79–80 Five members of Tirranna's crew were killed and others wounded. Filled with supplies for Australian troops in the Middle East, Tirranna was captured and sent to France.

On 11 July, the liner City of Baghdad was fired upon at a range of 1.2 km (0.75 mi). A boarding party discovered a copy of Broadcasting for Allied Merchant Ships, which contained communications codes. City of Baghdad, like Atlantis, was a former DDG Hansa ship, having been captured by the British in World War I. A copy of the report sent by City of Exeter was found, describing Atlantis in minute detail and including a photograph of the similar Freienfels, confirming that the "Japanese" identity had not been believed. Rogge had his ship’s profile altered, adding two new masts.[8]

At 10:09 on 13 July, Atlantis encountered a passenger liner, Kemmendine, which was heading for Burma. The crew on the Kemmendine opened fire on Atlantis with a 3-inch gun mounted on Kemmendine's stern. Atlantis returned fire, and Kemmendine was quickly ablaze. All the passengers and crew were taken off of Kemmendine, and Kemmendine was then sunk.[6]:16

Talleyrand and King City[]

In August, Atlantis sank Talleyrand, the sister ship of Tirranna. Then she encountered King City, carrying coal, which was mistaken for a British Q-Ship due to its erratic maneuvering caused by mechanical difficulties. Three shells from Atlantis destroyed King City's bridge, killing four merchant cadets and a cabin boy. Another wounded sailor later died on the operating table aboard Atlantis.[6]:18

Athelking, Benarty, Commissaire Ramel, Durmitor, Teddy, and Ole Jacob[]

In September, Atlantis sank Athelking, Benarty, and Commissaire Ramel. All of these were sunk only after supplies, documents, and POWs were taken. In October, the Germans took the Yugoslavian steamboat Durmitor, loaded with a cargo of salt. Yugoslavia was neutral at the time, but Captain Rogge was desperate for an opportunity for Atlantis to get rid of the POWs that had accumulated on board, so the ship was captured because it had been carrying coal from Cardiff to Oran before its current voyage.[6]:19 Captured documents and 260 POWs were transferred to Durmitor, which, with a prize crew of 14 Germans commanded by Lt. Dehnel, was dispatched to Italian-controlled Mogadishu.[9] Lacking sufficient fuel, the Durmitor resorted to sails and, after a "hellish" voyage, made landfall in Warsheikh, north of Mogadishu, on November 22, five weeks after departure.[10]

In the second week of November, two Norwegian tankers: Teddy and Ole Jacob were seized by Atlantis. On both occasions, Atlantis presented itself as HMS Antenor.[11]

Automedon and her secret cargo[]

At about 07:00 on 11 November 1940, Atlantis encountered the Blue Funnel Line cargo ship Automedon about 250 mi (400 km) northwest of Sumatra. At 08:20, Atlantis fired a warning shot across Automedon's bow, and her radio operator at once began transmitting a distress call of "RRRR – Automedon – 0416N" ("RRRR" meant "under attack by armed raider[7]").

At a range of around 2,000 yd (1,800 m), Atlantis shelled Automedon, ceasing fire after three minutes in which she had destroyed her bridge, accommodation, and lifeboats. Six crew members were killed and twelve injured.

The Germans boarded the stricken ship and broke into the strong room, where they found fifteen bags of Top Secret mail for the British Far East Command, including a large quantity of decoding tables, fleet orders, gunnery instructions, and naval intelligence reports. After wasting an hour breaking open the ship's safe only to discover "a few shillings in cash", a search of the Automedon's chart room found a small weighted green bag marked "Highly Confidential" containing the Chief of Staff's report to the Commander in Chief Far East, Robert Brooke Popham. The bag was supposed to be thrown overboard if there was risk of loss, but the personnel responsible for this had been killed or incapacitated. The report contained the latest assessment of the Japanese Empire's military strength in the Far East, along with details of Royal Air Force units, naval strength, and notes on Singapore's defences. It painted a gloomy picture of British land and naval capabilities in the Far East, and declared that Britain was too weak to risk war with Japan.[5]:117

Automedon was sunk at 15:07. Rogge soon realised the importance of the intelligence material he had captured and quickly transferred the documents to the recently acquired prize vessel Ole Jacob, ordering Lieutenant Commander Paul Kamenz and six of his crew to take charge of the vessel. After an uneventful voyage they arrived in Kobe, Japan, on 4 December 1940.

The mail reached the German Embassy in Tokyo on 5 December. The German Naval attaché Paul Wenneker had the summary of the British plan wired to Berlin, while the original was hand-carried by Kamenz to Berlin via the Trans-Siberian railway. A copy was given to the Japanese, to whom it provided valuable intelligence prior to their commencing hostilities against the Western Powers. Rogge was rewarded for this with an ornate Samurai sword; the only other Germans so honoured were Hermann Göring and Field Marshal Erwin Rommel.

After reading the captured Chief of Staff report, on 7 January 1941 Japanese Admiral Yamamoto wrote to the Naval Minister asking whether, if Japan knocked out America, the remaining British and Dutch forces would be suitably weakened for the Japanese to deliver a death blow; the Automedon intelligence on the weakness of the British Empire is thus credibly linked with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the attack leading to the fall of Singapore.[12][13]

At Kerguelen and Africa[]

In the Christmas period Atlantis was at Kerguelen Island in the Indian Ocean. There the crewmen did maintenance and replenished their water supplies. They suffered its first fatality when a sailor fell while painting the funnel. He was buried in what is sometimes referred to as "the southernmost of all German war graves".[5]:134

In late January 1941, off the eastern coast of Africa, Atlantis sank the British ship Mandasor and captured Speybank. Then, on 2 February, the Norwegian tanker Ketty Brøvig was relieved of her fuel. The fuel was used not only for the German raider, but also to refuel the German battleship Admiral Scheer and, on 29 March the Italian submarine Perla. Perla was making its way from the port of Massawa in Italian East Africa, around the Cape of Good Hope, to Bordeaux in France.

Zamzam[]

By April, Atlantis had returned to the Atlantic where, on April 17, Rogge, mistaking the Egyptian liner Zamzam for a British liner being used as a troop carrier or Q-ship—as she was in fact the former Bibby Liner Leicestershire—opened fire at a range of 8.4 km (5.2 mi). The second salvo hit and the wireless room was destroyed. 202 people were captured, including missionaries, ambulance drivers, Fortune magazine editor Charles J.V. Murphy, and Life magazine photographer David E. Scherman. The Germans allowed Scherman to take photographs, and although his film was seized when the prisoners returned to Europe aboard a German blockade runner, he did manage to smuggle four rolls back to New York. The photos later helped the British identify and destroy Atlantis.[14] Murphy's account of the incident and Scherman's photos appeared in the 23 June 1941 issue of Life.[15]

Post-Bismarck[]

After the German battleship Bismarck was destroyed, the North Atlantic swarmed with British warships. As a result, Rogge decided to abandon the original plan to return to Germany and instead returned to the Pacific.[2]:185–7 En route, Atlantis encountered and sank the British ships Rabaul, Trafalgar, Tottenham, and Balzac. On 10 September 1941, east of New Zealand, Atlantis captured the Norwegian motor vessel Silvaplana.

Atlantis then patrolled the South Pacific,[16] initially in French Polynesia between the Tubuai Islands and Tuamotu Archipelago. Without the knowledge of French authorities, the Germans landed on Vanavana Island and traded with the inhabitants. They then hunted Allied shipping in the area between Pitcairn and uninhabited Henderson islands, making a landing on Henderson Island. The seaplane from Atlantis made several fruitless reconnaissance flights. Atlantis headed back to the Atlantic on 19 October, and rounded Cape Horn ten days later.

U-68, U-126, and HMS Devonshire[]

On October 18, 1941, Rogge was ordered to rendezvous with the submarine U-68 800 km (500 mi) south of St. Helena and refuel her, then to refuel U-126 at a location north of Ascension Island. Atlantis rendezvoused with U-68 on 13 November, and on 21 or 22 November with U-126.[2]:208 The OKM signal instruction sent to U-126 ordering this rendezvous was intercepted and deciphered by the Allied Enigma code breakers at Bletchley Park and was passed on to the Admiralty, which in turn despatched the heavy cruiser HMS Devonshire to the rendezvous area.[17]

Sinking[]

Early on the morning of 22 November 1941, Atlantis was intercepted by Devonshire. U-126 dived, leaving her captain behind (he had gone aboard the Atlantis).[5]:190 At 08:40, Atlantis transmitted a raider report posing as the Dutch ship Polyphemus, but by 09:34 Devonshire had received confirmation that this was false.[18] From 14–15 km (8.7–9.3 mi) away, outside the range of Atlantis's 150 mm (5.9 in) guns, Devonshire opened fire.

After 20–30 seconds, salvos of 8-in (203 mm) shells began to reach Atlantis; the second and third salvos hit the ship. Seven sailors were killed as the crew abandoned ship; Rogge was the last off. Ammunition exploded, the bow rose into the air, and the ship sank.

After Devonshire left the area, U-126 resurfaced and picked up 300 Germans and a wounded American prisoner. U-126 began carrying or towing in rafts towards the still-neutral Brazil (1,500 km (930 mi) west). Two days later the German refuelling ship Python arrived and took the survivors aboard. On 1 December, while Python was refuelling U-126 and German submarine U-A,[19] another of the British cruisers seeking the raiders, HMS Dorsetshire, appeared. The U-boats dived immediately, and Python's crew scuttled the Python; the Dorsetshire departed, leaving the U-boats to recover the survivors. Eventually various German and Italian submarines brought Rogge's crew back to St. Nazaire.

Raiding career[]

| Name | Type | Nationality | Date | Displacement | Fate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scientist | Freighter | 3 May 1940 | 6,200 t | Sunk | |

| Tirrana | Freighter | 10 June 1940 | 7,230 t | Captured | |

| City of Baghdad | Freighter | 11 July 1940 | 7,505 t | Sunk | |

| Kemmndine | Passenger liner | 13 July 1940 | 7,770 t | Sunk | |

| Talleyrand | Motor vessel | 2 August 1940 | 6,730 t | Sunk | |

| King City | Freighter | 24 August 1940 | 4,745 t | Sunk | |

| Athelking | Tanker | 9 September 1940 | 9,550 t | Sunk | |

| Benarty | Freighter | 10 September 1940 | 5,800 t | Sunk | |

| Commissaire Ramel | Passenger liner | 20 September 1940 | 10,060 t | Sunk | |

| Durmitor | Freighter | 22 October 1940 | 5,620 t | Captured | |

| Teddy | Tanker | 9 November 1940 | 6,750 t | Sunk | |

| Ole Jacob | Tanker | 10 November 1940 | 8,305 t | Captured | |

| SS Automedon | Freighter | 11 November 1940 | 7,530 t | Sunk | |

| Mandasor | Freighter | 24 January 1941 | 5,145 t | Sunk | |

| Speybank | Freighter | 31 January 1941 | 5,150 t | Captured | |

| Ketty Brøvig | Freighter | 2 February 1941 | 7,300 t | Captured | |

| Zamzam | Passenger liner | 17 April 1941 | 8,300 t | Sunk | |

| Rabaul | Freighter | 14 May 1941 | 6,810 t | Sunk | |

| Trafalgar | Freighter | 24 May 1941 | 4,530 t | Sunk | |

| Tottenham | Freighter | 17 June 1941 | 4,760 t | Sunk | |

| Balzac | Freighter | 23 June 1941 | 5,375 t | Sunk | |

| Silvaplana | Motor vessel | 10 September 1941 | 4,790 t | Captured | |

| Total: | 145,960 t | ||||

References[]

- ↑ Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1922-1946

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Ulrich Mohr as told to Arthur V. Sellwood (1955 (2nd printing)). Ship 16: The Story of the Secret German Raider Atlantis. T. Werner Laurie Ltd., London.

- ↑ "LLOYD'S REGISTER, STEAMERS AND MOTORSHIPS". Plimsoll Ship Data. http://www.plimsollshipdata.org/pdffile.php?name=38b0354.pdf. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ↑ Muggenthaler, August Karl German Raiders of World War II Prentice-Hall, 1977, ISBN 0-13-354027-8, p16

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Rogge, Bernhard The German Raider Atlantis, Ballantine, 1956

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Duffy, James P. (2001). Hitler's secret pirate fleet : the deadliest ships of World War II (1. publ. ed.). Westport, Conn. [u.a.]: Praeger. ISBN 0-275-96685-2. http://books.google.com/books?id=H41M5lN5cGkC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Turner, L.C.F. (1961). War in the Southern Oceans: 1939-45. Oxford University Press. pp. 22.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Hilfskreuzer (Auxiliary Cruiser / Raider) Atlantis - The History

- ↑ Mohr & Sellwood 2009, p. 126

- ↑ Mohr & Sellwood 2009, p. 130. (Mohr and Sellwood refer to the region as "Somaliland", but Warsheikh is actually in the former Italian Somali, not the former British Somaliland).

- ↑ Mohr & Sellwood 2009, pp. 134–137.

- ↑ The sinking of Automedon

- ↑ Seki, Eiji. (2006). Mrs. Ferguson's Tea-Set, Japan and the Second World War: The Global Consequences Following Germany's Sinking of the SS Automedon in 1940. London: Global Oriental. 10-ISBN 1-905246-28-5; 13- ISBN 978-1-905246-28-1 (cloth) [reprinted by University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 2007 - previously announced as Sinking of the SS Automedon and the Role of the Japanese Navy: A New Interpretation.

- ↑ Noble, Holcomb B. (7 May 1997). "David Scherman, 81, Editor Whose Photos Sank a Ship". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/1997/05/07/arts/david-scherman-81-editor-whose-photos-sank-a-ship.html.

- ↑ Murphy, Charles J. V. (1941-06-23). "The Sinking of the "Zamzam"". Life. pp. 21. http://books.google.com/books?id=bU0EAAAAMBAJ&lpg=PA21&pg=PA21#v=onepage&q&f=false. Retrieved December 6, 2011.

- ↑ "Part 1—Royal New Zealand Navy". New Zealand Electronic Text Centre. http://www.nzetc.org/tm/scholarly/tei-WH2Navy-pt1.html.

- ↑ Hinsley, F.H. (1981). British Intelligence in the Second World War (Volume 2). Her Majesty's Stationary Office, London. pp. 166. ISBN 0-11-630934-2.

- ↑ HMS Devonshire 1929-1954, Neil McCart

- ↑ Blair, Clay The Hunters 1939-1942 (Volume 1): Hitler's U-boat War Modern Library, 2000, ISBN 0-13-978-0679640325

External links[]

Further reading[]

- Bergstrom, Marie Norberg. Zamzam Survivors Collection, 1932-2006. LCA Collection 10. Gustavus Adolphus College, Lutheran Church Archives, St. Peter, Minnesota.

- Duffy, James P. Hitler's Secret Pirate Fleet: The Deadliest Ships of World War II. Praeger Trade, 2001, ISBN 0-275-96685-2.

- Hoyt, Edwin Palmer. Raider 16. World Publishing, 1970.

- Mohr, Ulrich and A. V. Sellwood. Ship 16: The Story of the Secret German Raider Atlantis. New York: John Day, 1956. (Recent edition: Mohr, Ulrich; Sellwood, Arthur V. (2009). "Ship 16: The Story of a German Surface Raider". Amberley Publishing. ISBN 1848681151. http://books.google.com/books?id=htfLF3BQPxkC.)

- Muggenthaler, August Karl. German Raiders of World War II. Prentice-Hall, 1977, ISBN 0-13-354027-8.

- Rogge, Bernhard. The German Raider Atlantis. Ballantine, 1956.

- Schmalenbach, Paul. German Raiders: A History of Auxiliary Cruisers of the German Navy, 1895-1945. Naval Institute Press, 1979, ISBN 0-87021-824-7.

- Slavick, Joseph P. The Cruise of the German Raider Atlantis. Naval Institute Press, 2003, ISBN 1-55750-537-3.

- Swanson, S. Hjalmar, ed. Zamzam: The Story of a Strange Missionary Odyssey. 1941.

- Woodward, David. The Secret Raiders;: The Story of the German Armed Merchant Raiders in the Second World War. W.W. Norton, 1955.

Coordinates: 4°12′0″S 18°42′0″W / 4.2°S 18.7°W

The original article can be found at German auxiliary cruiser Atlantis and the edit history here.